Galton and Simpson - The Writers' Tale

As they were leaving the theatre [Tony Hancock] came up to them and making reference to a sketch they had written [he] said; "Did you write that sketch?" They nodded. "Very funny," said Hancock walking away. "Very funny." And the seeds were sown for the future of British comedy.

The Annals of British television comedy are littered with a long and distinguished list of writing partnerships whose work has brought moments of warmth and laugher into homes throughout the nation and beyond. But even amongst that illustrious list one particular combination of names which effortlessly commands the respect of their peers - and even more importantly that of the viewing audience itself - towers above all others.

Together, they created the televisual template that effortlessly weaves comedy and bittersweet tragedy into a satisfying whole. Humorous situations wedded to subtlety, deceptively complex and believable characters are their instantly recognisable and cherished hallmark.

They are the undisputed tsars of British TV comedy. Their names are Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, and this is not only their story, but also the story of British situation comedy.

Alan Simpson was born on 27th November 1929, south of the river Thames in Brixton. By the age of 19 he was working in a mundane job as a shipping clerk when he contracted tuberculosis. Ray Galton was born in Paddington on 17th July 1930, and by 1948 was working for the Transport and General Workers Union when he too contracted the killer disease.

During World War II and its aftermath, disease rates had soared among weakened populations. In particular, forms of tuberculosis - a disease which two hundred years ago was the greatest killer the country had ever seen - were widespread. In the early 1950s, there were thought to be around 20 million cases worldwide. In England and Wales around 50,000 cases a year were being reported. This painful condition, spread by a micro-organism, thrived in crowded and unsanitary conditions in many areas of the UK, and could lead to total disability, and in many cases those who were infected were not expected to survive.

Treatment, when available, was admittance to an isolation hospital, and might take up to three years. In 1948 Ray Galton was admitted to the Milford Sanatorium in Surrey, where the other patients were mainly older men straight out of the armed forces. Some time around August, Ray was laying on his bed in a small four-cubicle room when Alan Simpson walked past. "When Alan went past, the room went dark, because he was a big man - about 6ft 4in and 18 or 19 stone. I saw this shuffling figure with a big brown dressing gown on, with the collar turned up, going by swinging his toilet bag on his way to have a wash. I thought, "Who the hell's that?", because you expect everyone in a sanatorium to be thin and weedy, and he was the biggest guy I'd ever seen."

As the hospital staff liked to keep patients of a similar age together, Alan was soon moved into the same cubicle as Ray. Another who shared the space with them was Tony Wallis, a skilled electrician and something of a radio buff, which proved to be quite a relief for Alan and Ray. Up until then the only form of entertainment for them was a radio which could only tune into one channel. Although it was strictly against the rules, the staff allowed Tony to rig up his own receiving equipment utilising an RAF eleven-fifty-five radio from a Lancaster. By the time Tony had finished every patient had the choice of the BBC Home Service the Light Programme and the hospital's own radio station.

Alan and Ray listened avidly to all the comedy shows and Tony managed to tune into another network, probably a forces one, where they heard US comedy shows such as The Phil Harris Show and The Jack Benny Show as well as more obscure (to British listeners) shows such as Duffy's Tavern, Ozzie and Harriet and The Great Greensleeve. These were all formats that were deemed unsuitable by the BBC.

Not content with stopping there, Tony Wallis was allowed to convert a broom cupboard into his own studio and soon the patients formed their own radio committee to decide on the type of shows they wanted to broadcast. These were mainly copies of BBC shows and also included record requests, with music supplied courtesy of the hospital charities. Then Alan and Ray offered to write six 15-minute comedy shows, and the committee accepted. The shows were a satire on hospital life and proved popular with both staff and patients, although after just four shows the material dried up.

Seeking encouragement and advice on writing comedy elsewhere, Alan and Ray decided to write to the BBC for their help. One of their favourite home-grown series at this time was Take It From Here starring Jimmy Edwards and Dick Bentley. The writers were Frank Muir and Denis Norden and that's whom Alan and Ray decided to address their letter to. In reply they were told to send any material they had to the BBC's script editor, Gale Pedrick, who was always on the lookout for new talent. However, Alan and Ray didn't do much writing together following their brief hour of comedy and about a year later both men had sufficiently recovered to be allowed home from the sanatorium. Alan went back to work but Ray, who was let out four or five months after him, was still too frail to return to work. The pair continued to see each other socially but didn't write together again until an amateur church concert party, where Alan had been a member during his teens, approached him and asked if he had any material they could use. Alan asked Ray for his help and the two men got together at Alan's mother's house for some evening sessions in which they put together a number of topical sketches. At that time they also laid down the format for their future partnership, with ideas being thrown backwards and forwards until they both agreed on a line. Only then would it be committed to paper and it was Alan Simpson who did the actual writing.

Having started working together again, Alan and Ray wrote a sketch based on the last segment of Take It From Here, which was usually a spoof of something popular at that time. It was a ten-minute sketch, their target was Captain Henry Morgan, the 17th century privateer, and having remembered the advice they got from Muir and Norden they sent it to Gale Pedrick. Ray and Alan remember: "A pirate sketch seemed ideal for Joy Nicholls, Dick Bentley and Jimmy Edwards and Henry Morgan seemed the ideal subject matter. The whole purpose was to give Gale Pedrick, the script editor at the BBC a sample of what we could write."* Within a few weeks a reply came which said: "Don't read more than appears on the surface of this letter but we read your script and were highly amused. Make an appointment with my secretary and maybe I can point you in the right direction." When Alan received the letter he made his way over to Ray's house and the two of them got drunk. "We showed all our friends that letter and even if nothing else had happened, we would still be showing that bit of paper to people saying, 'Look, we nearly made it.'"

They made an appointment to see Pedrick as instructed, and found him to be very helpful. Even though he could not promise any immediate commissions he circulated the script for them and put them in touch with a few producers. One of these was Roy Speer. The script was left on his desk while he was producing a show called Happy Go Lucky starring Derek Roy, who in 1951 was a big star on radio along with Frankie Howerd. Derek happened to be in Roy Speer's office one day and picked up the script and started reading. He said, "Who wrote this, because there is some good stuff here?" Before Roy had finished reading the first page he asked Speer to call the young writers up to Broadcasting House for a meeting. Galton and Simpson were duly called up and on meeting Derek Roy came to an agreement whereby they would write jokes for him. For every one he accepted they would be paid five shillings. They returned to Alan's mum's place and bashed out a bunch of one-liners, which they describe as being very much in the Bob Hope style. They would take them round to Derek's flat where he would go through them one by one and say "Yes, yes, no, yes, no, no, yes, yes," then call his secretary in and say "five". Out would come the cash box and they were paid their 25 shillings or whatever it amounted to, and they'd go away and split it. As far as Galton and Simpson were concerned, this now made them professionals.

Despite its title Roy Speer's show was neither happy nor lucky. The show was conceived by Jim Davidson, who at that time was head of variety at the BBC. It was written as a vehicle for Derek Roy because he'd never starred in his own series before and it was felt that he deserved a chance. It also featured a number of up-and-coming comedy stars such as Graham Stark, Bill Kerr, Peter Butterworth and a comedian making a real name for himself, Tony Hancock. Speer was struggling to find writers. In spite of Derek Roy's admiration for Galton and Simpson, he was reluctant to give a 50-minute sketch show over to two new and untried talents. But the show was a complete flop anyway. During the 13-week run the pressure on Speer became increasingly unbearable. He was even accused of deliberately trying to sabotage the production because the BBC management had suggested it. There were also totally unfounded accusations of the producer taking bribes from agents, and all this led to Roy Speer having a nervous breakdown before the end of the series. There were still three weeks to go when Speer's departure was announced. The man put in charge for those last shows was Dennis Main Wilson. The first thing he did was sack all the writers - except for Galton and Simpson. "He came up to us and said, "You two tall blokes, are you writers?" And we said, "Yes", so he said, "all right, you write the show." We said yes even though we didn't think we could do it, because we knew if we had said no, we'd have been finished. Our only saving grace was that the show was so bad that it couldn't have been any worse." They were paid forty guineas a show and on the day the first cheque arrived Alan Simpson quit his office job and bought a typewriter.

The final Happy Go Lucky was recorded at the Playhouse Theatre in Lower Regent Street, London. It was here that the writers had their first conversation with Tony Hancock. As they were leaving the theatre the star came up to them and making reference to a sketch they had written about a children's party said; "Did you write that sketch?" They nodded. "Very funny," said Hancock walking away. "Very funny." And the seeds were sown for the future of British comedy.

A few weeks later, Hancock telephoned Galton to ask if they would write single five-minute sketches, which he could use on various variety shows. He offered them half his fee. It proved to be a very generous gesture: for his next show he earned £50.00 Just as importantly, Galton and Simpson were now growing in reputation within the BBC. They were offered the chance to write the last six shows of a series called Calling All Forces which up until then had been done by the writing team of Bob Monkhouse and Dennis Goodwin. Calling All Forces was the biggest Radio show on the air, but the gruelling schedule had left Monkhouse and Goodwin exhausted and in need of a well-deserved holiday. Tony Hancock, meanwhile, was playing second banana to Charlie Chester. After these six shows the BBC, impressed by Galton and Simpson's scripts, decided to continue the series under a succession of names, firstly Forces All-Star Bill and then All-Star Bill and finally Star Bill. It had a different guest comedian every week, but Tony Hancock was now the star. "It ran for another two or three years," says Alan Simpson, "by which time we had written for every comic in the country. We were still in our early 20s at this time, but we were getting known within the business. So much so that Spike Milligan asked us to form a company called Associated London Scripts with him and Eric Sykes."

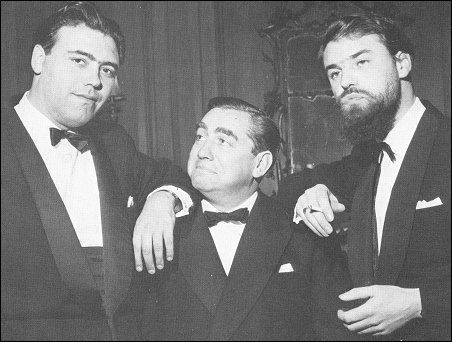

Dennis Main Wilson (left) with Bob Hope, Bob Monkhouse and Denis Goodwin

Dennis Main Wilson, who had given Galton and Simpson their first chance to write a full radio show by themselves, was also the producer of Star Bill. Main Wilson had also produced the legendary Goon Show and would become one of the most influential people in the entire history of British situation comedy. Galton and Simpson approached him and asked if they could do a half hour show with Tony, rather than the sketch show. "We wanted to do a storyline all the way through that was character based. We were adamant we wanted no jokes or silly voices. And unlike The Goon Show and so many others of the time, we wanted no musical breaks." It was a concept that was totally new. Main Wilson, who was 29 at the time and was very open to new ideas, thought it was a great chance to do something completely different. On 1st May 1953 Wilson sat down and wrote a memo that would change the course of British situation comedy forever. 'I believe', he wrote 'we can entertain most of the people, most of the time, without having to drop our sights - either intellectually or in terms of entertainment.' This thirty-minute situation comedy would follow the misadventures of a central character and his associates, based on reality and truth as opposed to jokes, 'merry quips and wheezes'. When his memo arrived on the desk of the BBC's head of variety that same afternoon it sparked weeks of debate. Many doubted the viability of a show so far removed from the accepted format that Main Wilson was forced to submit further memos over the ensuing weeks. 'The comedy style will be purely situation in which we shall try to build Tony (Hancock) as a real-life character in real-life surroundings. There will be no 'Goon' or contrived comedy approaches at all.'

On Tuesday 2nd November 1954, at 9.30 pm the British public were treated to the first Hancock's Half Hour. Teamed with Sid James and Bill Kerr that first Hancock show also gave a break to another comedy performer on his way to immortality, Kenneth Williams. An Audience Research Report for the show indicated that it had attracted 12 per cent of the adult population - 13 per cent down on The Al Read Show, the series that had previously been broadcast in the same slot. However, it proved good enough for the BBC to decide to continue with the first series, but without commitment to a second one. The first series of Hancock's Half Hour ended on 15th February 1955 with ratings climbing steadily. A second and third season were subsequently ordered, with the BBC confident enough in their star and his writers to commission twenty episodes for season three. Each script was conceived, written and then delivered within a week: a furious working pace. It was also during this series that Hancock's legendary home of 23 Railway Cuttings, East Cheam, was established. By the end of that third series the BBC were facing competition from their first television rival. ITV had begun broadcasting in September 1955 and the BBC was desperate to come up with new TV material in what was the beginning of a hot ratings war. ITV were also doubling all the BBC's wages and the Corporation was in danger of losing Hancock at one stage. Around this time Hancock was under contract to Jack Hylton to do a stage review, which he didn't want to do. When he tried to get out of it Hylton would only agree on condition that Hancock do a television series for him at ITV. Eric Sykes was the writer for this series but as good as Sykes was, it was only really Galton and Simpson who knew how to get under the skin of the persona they had devised for Tony. Tony asked them to write the last three episodes but they were under exclusive contract to the BBC who flatly refused to allow them to write for their rival. When it was pointed out that it was in the BBC's best interest that Tony have a successful series, because a flop on ITV would only harm his reputation, they relented and let them write the episodes as long as they didn't take a credit for them. Free of his contract, Hancock able to return to the BBC. "The only problem was," says Alan Simpson, "ITV had doubled our money, so the BBC had to match it. From then on we never looked back."

G&S with Sid James, Hancock and Hattie Jacques

Reaction to Hancock's first BBC series was decidedly cool. Even though around 56 per cent of the British television-owning public tuned in, many felt that the transition from radio to television was 'disappointing'. However, ratings climbed steadily and a second series was commissioned. Over the next three years Hancock's Half Hour became the yardstick by which all other British sitcoms would be measured for decades to come. After the sixth radio series Galton and Simpson scripted a movie for Tony Hancock called The Rebel. "Tony got it in his mind that he had to get away from the double act that everyone perceived with him and Sid." says Alan Simpson. Sid James didn't have to rely on Hancock. He was doing up to ten films a year, but in the public's consciousness they were always together and Hancock was troubled by this. "Tony did not want it to turn into a Laurel and Hardy. He also wanted to be big internationally, which he got a taste of by doing The Rebel, and working with George Sanders. Following this taste of 'going it alone' Tony decided to drop Sid James for what turned out to be the last BBC TV series. He wanted to get as far away as possible from the image that Galton and Simpson had built for him. "This meant getting him out of East Cheam, losing the Homburg hat and getting rid of Sid. We also got rid of the half hour and just called it Hancock. People used to say that he was never the same after Sid James left, but four of the episodes in that series were the most famous we ever did," says Ray Galton. "You ask people to name any Hancock episodes and they will usually say The Blood Donor, The Lift, The Radio Ham, The Bowmans."

The series had immense pulling power and many pubs complained that customers would stream out twenty minutes before the broadcast of the latest 'Hancock' to ensure that they got home in time and were comfortably in front of the television before the show started. By the time the series finished, on 30th June 1961, one in three of the television-watching adult population had tuned in to what was the final chapter of a comedy era. For Tony Hancock would never rise to such heights again. Galton and Simpson, on the other hand, would.

NEXT: Galton and Simpson - Part 2

Article: Written by Laurence Marcus (January 2006 updated 2019). *Special thanks to Tessa Le Bars, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson. Additional material: Peter Henshuls. Edited by Pippa Gwilliam.

Tony Hancock was born in Southam Road, Hall Green, Birmingham but, from the age of three, he was brought up in Bournemouth, Hampshire, where his father, John Hancock, who ran the Railway Hotel in Holdenhurst Road, worked as a comedian and entertainer.

After his father's death in 1934, Hancock and his brothers lived with their mother and stepfather Robert Gordon Walker at a small hotel called Durlston Court, in Gervis Road, Bournemouth. He attended Durlston Court Preparatory School, part of Durlston boarding school near Swanage and Bradfield College in Reading, Berkshire, but left school at the age of fifteen.

In 1942, during the Second World War, Hancock joined the RAF Regiment. Following a failed audition for the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA), he ended up on the Ralph Reader Gang Show. After the war, he returned to the stage and eventually worked as resident comedian at the Windmill Theatre, a venue which helped to launch the careers of many comedians at the time, and took part in radio shows such as Workers' Playtime and Variety Bandbox.