Ray Cusick Interview

"(Terry Nation) didn't want me around."

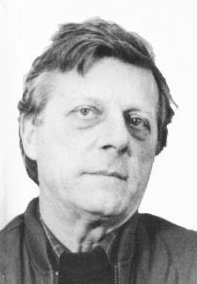

In 2001, for the Television Heaven website, we spoke to BBC designer Ray Cusick about his career, about his design of the Daleks and how Terry Nation went back on his word.

In television, as well as film and theatre, praise invariably goes to the director and the writer -but not to one of the central unsung heroes of any production, which is more often than not the designer. In Ray Cusick's case that is certainly true. For many years his contribution to British television history went largely unsung outside of that industry. When Jon Pertwee was asked to select the winning entry to a competition on the BBC's own Pebble Mill show back in the 1970's, which demanded an answer to the question "Who created the Daleks?" the winning answer was given as scriptwriter Terry Nation. This answer had been the accepted response for many years, but was in fact quite incorrect. And further more Pertwee set the record straight there and then by revealing to the live audience what most Doctor Who fans had known for many years, that the true credit belonged to veteran BBC designer Raymond P Cusick. On 21st January 2001 we made our way across rain-drenched London to meet Ray and gain an insight into his background and professional history.

Ray was born in the York Road Hospital by Westminster Bridge, which was originally built for military personnel, although it's now closed. He was baptised in St. Patrick's, Soho Square. Whilst still at school Ray became interested in art and began attending evening classes. "As soon as I walked into the art school I really felt at home," recalled Ray. "My father was very concerned. He was in the RAF at the time and he wanted me to be something proper, like a civil engineer, so I started a course at the Borough Polytechnic, which was basic science and maths to start off with...and I hated it! So my way out was to volunteer for the army ...and I hated it!" Following a period stationed in Palestine, Ray returned home where he completed a teachers training course. However, before going into teaching he got a job in Rep at Cardiff's Prince of Wales Theatre. The job lasted for nine months but Ray looks back on it now with less than happy memories. "It was such a disaster. I came back to London and met a friend of mine from teacher training college and he said 'Why don't you teach.' So I thought 'I'll do it for a while to sort myself out.'"

Taking on a teaching job was nothing more than a stepping-stone for Ray and he soon made the move back into theatre again. But the move back proved to be less than straightforward. "I used to buy The Stage for situations vacant, and it was a time when television was beginning to expand, it was the late 50's." Ray noticed an ad from Granada Television for designers on a show called Chelsea at Nine, which came from the Chelsea Palace Theatre. "So I applied for the job and went for an interview and they said, 'Can you start yesterday?' to which I replied, 'No, I'm teaching, I have to give notice.' 'Right,' they told me, 'give notice, come back, we need you.' Which I did. But when I went back it was a case of 'Who are you?' So I said 'Brody (I can't remember his first name) sent for me.' And they said 'who's Brody?' Well he was a Canadian and apparently he'd gone back to Canada and they told me that he had no right to offer me the job in the first place! So I dashed out and bought another copy of The Stage and there was another job going at Wimbledon Theatre for a designer, so I went there and stayed for nearly three years."

Ray's next step was to prove a crucial one. He applied for a job at the BBC, and was accepted, "but not on a full time basis. Everyone started as a Holiday Relief, on a temporary contract." At this time the BBC had lost its monopoly on broadcasting to the British public and was facing a serious challenge from the rapidly established Independent Television companies. "Television was expanding and they were building studios all over the place. And they were desperate for staff. A lot of the BBC staff left in droves because they were offered decent salaries whilst the BBC were only paying in shirt buttons. 'It's the honour of working for the BBC'."

"I actually was told this once. 'You're complaining, but there are people who would give their right arm to work for the BBC.' But a lot of people said 'stuff the BBC', and went!" But it was still an exciting time to be part of the Corporation and there were many opportunities both in front of and behind the cameras. "The actual people that made the programmes were entrepreneurial; developers; they were full of ideas." After learning his trade as an Acting Designer on such shows as Sykes and Hugh and I, Ray got the chance to become an integral part of one of those innovative new ideas.

Ridley Scott had been assigned to do the set designs for the relatively new science fiction series Doctor Who. The second story, which went under the working title of The Mutants, was set on an alien world and required a design for a creature unlike anything previously seen. "It was at the pre-planning stage. I'd just finished a children's serial called Stranger on the Shore, and I was scheduled to do a whole block of filming. You couldn't do a lot of special effects stuff in television studios. We did it at our own film studios at Ealing. There's a world of difference between film and TV as any cameraman will tell you, and Ridley Scott was only going to do the studio work, but when Verity Lambert, the producer, heard this she was a bit put out because of continuity. She thought it would be wiser to have the same designer, but Ridley wasn't free to do any of the one's after that."

Although The Mutants was only in the pre-planning stage, Ray still had to come up with a design for the serial's monsters; the Daleks. He knew he didn't want the traditional man in a silver suit with a mask on look. Following several designs and discussions with other members of the production staff, Ray came up with a unique design, one that instantly captured the imagination of an entire generation of children. "Before rehearsals started the cast and other members brought their children along and they were shown the Daleks and talked to the Dalek Operators, but then when rehearsals started the Operators got into the Daleks and started moving, and at that point all the children screamed and ran out of the studio!" The desired effect had unquestionably been achieved. The rest of the design work for this story was dictated by the creatures themselves, "If the script asks for a city then you design a city, but it's up to you how you do it. But when I designed the Dalek City for example, I designed it to suit the Daleks and not human beings, and that's why when the human beings walked through corridors they had to stoop, because the Daleks were low, and (the set) was designed to the maximum height of the Daleks, 5" 2'."

Doctor Who received very little preferential treatment, especially when it came to time and budget. "Because they just lumped it into that children's...well, what they called family entertainment, like Stranger on the Shore, and almost on the same ridiculously low budget. The four Daleks were made for something like £250.00."

With the broadcast of The Dead Planet as The Mutants was finally titled, Dalekmania swept the country -with all the plaudits going to writer Terry Nation. There was recognition for Ray's work within the BBC and then there was talk of a film. "Terry Nation said to me 'Ray, leave it to me, I'll see you get the job.' Of course that's the last thing he wanted. He didn't want me around." Ray continued to work on Doctor Who for the next few years, but eventually found the schedule too punishing. "It was 25 hours a day, 8 days a week for two-and-a-half to three years. That's why I came off it." Following his departure Ray was eager to work on a different type of show altogether. "I had a chat with one of the chief designers; he said 'Well, I don't know what we can give you.' I said okay, but I'm not a science fiction fan, that was my job and being professional I did it. 'As long as it's drama' I Said, 'I don't mind.' And immediately he put me on a series of single science fiction plays called Out of the Unknown. I did two of those... and in one of them we had the TARDIS!"

Following this, Ray got the chance to work on two period pieces, which allowed him to indulge in his love of history. "I did a couple of plays, Journey's End (which was written in 1928 by R. C. Sherriff, and based on his experiences as a captain during the First World War), and a Noel Coward play that he wrote based on Journey's End, starring a young Keith Baron, all set in the trenches in 1914." It was round about this time that Ray also took on the role of director, albeit for a very short period. "The BBC used to run production courses for foreign students and also for members of their own staff. A three-month course, quite intensive, and the goal at the end was you produced a short piece on film. You were allowed half a day to shoot it, so you would end up with something like three or four minutes of edited film and you also did a studio production lasting about twenty-five minutes. The group I was in were the first to have synch sound on the film course, so I wrote a script myself and I wrote a script in fact of the television production, and you'd get directors and producers to come and see it, and I was offered work on a show called The Newcomers which came from the BBC's Birmingham studios, and I did 3, which woke me up. It was a shock. I'd never worked so hard in all my life!" By now in his early forties, Ray decided against a change of career. "I'd been designing all my life and to suddenly start on a new career ...well, every cobbler should stick to his own Last, as my mother used to say."

Ray then worked on some classic BBC serials such as The Pallisers, Duchess of Duke Street, When the Boat Comes In and To Serve Them All My Days. Many of these shows were run on a very tight budget. The Pallisers in particular was only funded to the tune of £50,000. "Well, it had a small budget, but I worked with a director who's no longer with us, and he said 'stick with me, I'll see you get everything.' So I stuck with him and gave him what he wanted but there was no further money coming up front. I got into terrible trouble. It wasn't the usual (permissible) ten per-cent; it was a very heavy overspend. It was the beginning of when the BBC was trying to hold the reins; it was running away with itself."

So did he find the small budgets that the BBC allotted each series, and for which they became infamous, was creatively frustrating? "You say to a director 'But there's not enough money' and he says 'use your imagination, we know that you can do it.' And you get these clever directors who wanted to shoot the Battle of Waterloo with twenty people and you get lots of legs. When we did When the Boat Comes In we did the Jarrow March, we had twenty extras in ill-fitting suits, and wardrobe had supplied them with beautiful boots, and of course (in real life), they had rough old boots which they wore out before the end of the march and we filmed them dancing around the studio and you just had endless boots walking past, and that was the Jarrow March. That sort of thing doesn't fool me or the viewers for a minute, especially today, people want to see that march going on to the horizon."

From this point of view it's possible that Ray may have been happier working with the multi-million dollar budgets that feature films could offer. But he decided that it was too big a risk, even though some of his colleagues did make the transition. "When I met them afterwards they'd be biting their nails and nervous, 'what is it?' I'd ask. 'Well, I'm just about to finish this picture and I haven't got another one to follow." So it was the assurance of job security and a steady salary that ultimately persuaded him to continue with the Corporation for the remainder of his professional life. He finally quit the BBC to retire in 1988 following a long and distinguished career, and having worked there during what is generally regarded as a 'golden age' for British television. Did he personally see it in that light? "No, because it was all new, we were actually making it, so you don't know you're living through it and you think it's going to go on forever. It's like the Battle of Britain; it's only afterwards that you're told 'that's the Battle of Britain.'

Does Ray feel that there is a major difference between the BBC of yesterday and the BBC of today? "The sort of power or influence that producers had then...I don't think it exists now, it's more of a committee. At the Beeb you had teams, and often when I was going to work on a programme I'd say 'who's the director?' and they'd say 'so-and-so' or it would be a particular cameraman and you'd end up working with the same people you'd worked with before, which means you don't have to explain everything. If you have an idea, well, they know they can leave it to you because they know how you work." So has British TV lost its creativity? "Yes, of course it has. Behind the scenes you've got this vast army of heads of department, admin, god knows what, who are there to run the BBC regardless of programmes, and I was once involved in admin myself when I was an acting chief designer and I came to the conclusion that if the BBC stopped overnight it would take about 2 or 3 years to run down, -they'd still go through the motions."

Next: Matt Zimmerman Interview

Laurence Marcus interviewed Ray Cusick in 2001