John Logie Baird - Television, Secret Experiments, Sabotage, Lies - Chapter 3

John Logie Baird - Chapter 3: Television Discovered

In March 1925, Mr Gordon Selfridge Junior got to hear of Baird's experiments that had resulted in the transmission of simple "shadowgraphs", and after making some enquiries he called on Baird at Frith Street. He was given a demonstration and saw transmitted from one room to another a crude outline of a paper mask. Tiltman's book explains: 'This was made to wink by covering the eyeholes with white paper, and it could be made to open and close its mouth by covering and uncovering the slot corresponding to the mouth opening.' Selfridge was impressed enough to arrange for Baird to give personal demonstrations of the new device for three weeks at his Oxford Street store. He agreed to pay the inventor £25.00 a week and supply the necessary electrical current and material. Baird accepted this unexpected windfall without reservation and Selfridge arranged for a circular to be issued advertising the demonstration in April 1925.

These demonstrations at Selfridge's showed nothing more than simple outlines and nothing in the shape of a human face, for as far as is known Baird had still not created "true television". In spite of the publicity the inventor and his invention was receiving, his partner, Will Day, grew tired of the lack of progress and told Baird that he would not invest one penny more. By day and night Baird slaved away in Frith Street convinced that he was within grasp of the vital missing link that would allow him to progress to the next stage of development. But without further funding Baird found himself almost on the point of giving up. He was now living in poverty. His health again began to suffer, and in spite of trying to arouse interest in his project from the offices of several newspapers, he found that he was now being dismissed as nothing short of a crank. To save himself from starvation he had to realise a few shillings by selling vital parts of his apparatus. Finally, his work had stopped.

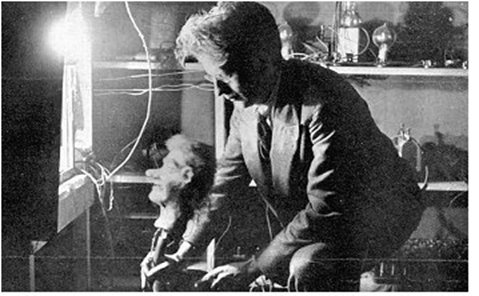

When his family in Scotland discovered the conditions that John Logie Baird had been living in, they responded by purchasing £500.00 worth of shares in the little-known company now formed as Television Ltd. Baird immediately set about remodelling his apparatus and improving its optical system. The effect of this rendered the transmitted images more sharply than ever before but still with no detail. On the evening of 1st October 1925 Baird concluded a series of tests using the latest light-sensitive system that he had devised. The problem that Baird (and all other experimenters) had with the selenium cell was that it took a little time to respond to changes in light. The result was that the picture that he was attempting to transmit appeared on the screen as a formless blur of light. "I decided to see what could be done about the time lag", he later recalled. "I was using a rather dilapidated ventriloquist's doll that I'd named (Stookie) Bill as the object of my experimental transmissions. What was happening was this; when the light fell on the cell, the current, instead of jumping instantly to find its full value, rose slowly and continued rising as long as the light fell on it. Then, when the light was cut off, the current did not stop instantly but only stopped increasing and began falling, taking quite an appreciable time to get to zero.

"While watching this effect, it occurred to me that it could be cured or mitigated if I superimposed a curve representing the time rate of change upon the curve of the current with time. By putting a transformer into the current I should in effect accomplish this. The moment the light fell upon the cell there would be a changed from no current to current. And although the current would be small, the rate of change would be great."

The following morning, 2nd October 1925, was spent fitting the device and generally overhauling the equipment. Early on this Friday afternoon he placed Bill in front of the transmitter. Normally the doll's head came through on the receiving screen as a white blob with three black blobs marking the position of the nose and eyes. But on this occasion Bill suddenly appeared as a recognisable image, with shading and detail. The nose, eyes and eyebrows could be distinguished, and the top of the head appeared rounded. In his autobiography, Baird described this historic occasion: "The image of the dummy's head formed itself on the screen with what appeared to be almost unbelievable clarity."

Baird rushed downstairs where he came across William Taynton, a young office boy working on the floor below. Baird convinced the office boy to go upstairs and sit before the transmitter where enormous electric lamps gave out a glaring light and a great deal of heat. Baird rushed to the next room to see the results on his receiver but was dismayed to discover that it was entirely blank. No amount of adjusting the equipment would produce a picture, and a crest-fallen Baird went back to the transmitter. Under the intense heat, Taynton had moved away from the lamps and had moved out of focus. In what Baird described as "the excitement of the moment" he gave the boy half-a-crown (12½p) and explained that he must remain exactly where placed. This time Taynton's image appeared on the receiving screen. This is the often-reported story of how Baird first came to televise a living person for the first time, and accordingly, Taynton has gone down in history as the first person to appear on television. It is the official version that Baird supported himself and as such offers a neatly romantic tale for the history books. However, if we are to believe that Baird had in fact achieved television transmission years before this, then we may begin to suspect that this version of events was merely part of another smokescreen that Baird created in order to safeguard the secrets of his work. Through the years many have disputed the accepted version of events. John Hart, who had been one of Baird's helpers, always claimed that he was the first man to be televised. A doorman at a London club claimed for years that he was first, and in 1951, at the unveiling of a plaque to Baird at 22 Frith Street, a Mr J. E. Hamelford showed the assembled party a letter, written and signed by Baird (since proved to be genuine), saying that Hamelford was the first person to be televised.

With new capital coming into Baird's venture, and the money from his family in Scotland, the inventor was able to move into larger premises at Motograph House near Leicester Square. It was only now that Baird knew the 'luxury' of employing his own staff. William Taynton was employed as his office boy and towards the end of the year a Mr. Clapp was taken on as his first technical assistant. Steady research now led to gradually improved results and as Baird worked towards turning his apparatus into a commercial success, he began to achieve results with the use of normal lighting.

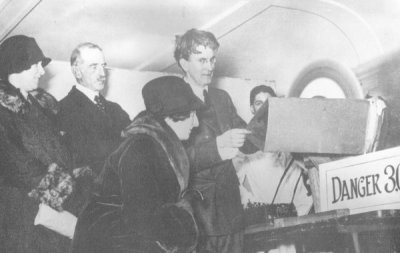

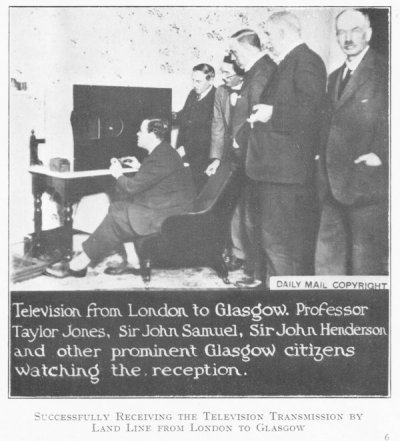

Baird's success and growing reputation caused his contemporaries to redouble their efforts. In April 1927 the American Telephone and Telegraph Company staged the first television demonstration over any distance outside of England. Images were sent by wire for a distance of 200 miles between Washington and New York. The demonstration was staged amid great publicity and elaboration and occupied the services of about 1000 engineers. Baird made no comment on the American test but the following month he arranged his own demonstration when pictures were transmitted over the 438 miles of telephone line between London and Glasgow.

The sound made by Baird's images always fascinated him. He claimed that he could distinguish between a cabbage or a face, a moving or a still image, simply by the sound it made. This led to his recording the signals with a needle cutting into a wax disc responding to signals from the microphone. In October 1926 Baird applied for British patent No. 289,104. In January 1927 he applied for a second patent No. 292,632 to provide for metal discs. He planned to later market these recordings and called his invention 'Phonovision.' A few of the discs that Baird made still survive and are a unique record of early television footage.

On 27th September 1927, the world's first television association was formed. The Television Society of Great Britain was founded to "further the development of problems associated with television, Noctovision, Phonovision and allied subjects." By now Baird was operating 2.T.V., the world's first television transmitting station between Motograph House and a receiving station at Green Gables Harrow. Also, by the end of the year Ronald F. Tiltman was approached by a group of businessmen to organise and control the publication of the world's first television journal. Quite simply titled Television the first issue came out in March 1928 priced 6d.

Sometime between November 1926 and April 1927 - Baird and his assistant, Benjamin Clapp came up with the idea to rig up a receiving station and television receiver in America and transmit the pictures over telephone lines from Baird's laboratories in London, to Clapp's house in Surrey where he operated a powerful transmitter station. Prior to any press demonstration, careful transatlantic radio tests would need to be conducted, and Clapp's surviving station logbooks depict how these were done three times a week. At one point, they attempted to transmit the image, recorded on a gramophone disc, of one of Baird's ventriloquist dummy test subjects. Reception was not successful, possibly because of problems associated with the synchronising arrangements. The 'Phonovision' disc which is the only disc known to depict images of 'Stookie Bill', still exists.

Although 1927 seemed to be a good year for Baird and the future development of television, the autumn of 1928 saw the beginning of a year of strife, which would place Baird's achievements before the public. The inventor would face a number of lies, half-truths and criticisms in the very country that should have been singing his praises.

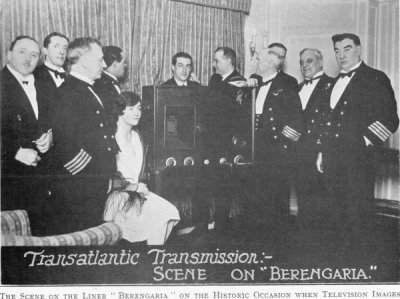

1928 had got off to a decent enough start. On 9th February Baird spanned the Atlantic when he succeeded in transmitting images from London to Hartsdale, a suburb of New York. Two days later the New York Times wrote of this success: 'Baird was the first to achieve television at all, over any distance. Now he must be credited with having been the first to disembody the human form optically and electronically, flash it piecemeal at incredible speed across the ocean, and then reassemble it for American eyes.' The transmission across the Atlantic was followed almost immediately by the transmission to the ship 'Berengaria' in mid-ocean, where the chief wireless operator, Mr. Brown, was able to see his fiancé in Long Acre, London.

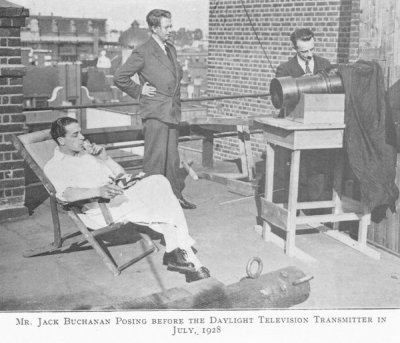

By June, Baird managed to accomplish television by daylight on the roof of the Baird laboratory. Writing in Television Magazine, Sir Ambrose Fleming reported on this 'very striking advance': In this vast improvement it is not necessary for the face or the object, the image of which is to be transmitted for television, or "televised" (if one may venture to coin such a word), to be scanned by a brilliant beam of light traversing it. The object whose image is to be transmitted can be simply placed in diffused daylight, just as if the ordinary photograph of it had been taken.' In August, Baird laid on two more demonstrations - television in natural colour using red, green and blue filters and the transmission of 3D, or 'stereoscopic' television. It is possible that Baird was trying to juggle too many plates at the same time. This alone may have been enough for some to cast doubt on his achievements, when refining the basic principles of television may have served him better.

The autumn saw the opening of a year of contention over the troublesome questions of broadcasting facilities, which would place Baird's achievements before public scrutiny and cause Baird himself much anxiety as he defended himself from baseless criticism and lies. Writing to the press in 1928 one supporter of Baird wrote; 'The possibilities of television are so immense that it should have been regarded as a question of national honour to have backed substantially any inventor whose discovery in this field was based on the established laws of science and whose results could be demonstrated.' And yet, while Baird's achievements were recognised to the full abroad, in England his achievements were met with disheartening apathy and obstruction by sections of the press who claimed that British television had no commercial future, that no further advance was possible and that transmissions on a waveband of 10 kilocycles were impossible. The BBC could have stepped in at this point and put an end to the controversy by fully supporting Baird, as indeed they had secretly granted permission for the inventor to use their 2LO station for experimental purposes as early as 1926, at which time Baird did transmit on the 10 kilocycles waveband. The permission to experiment though was given with the strict proviso that the fact could not be disclosed by Baird for propaganda purposes, and even in light of the criticism Baird was facing in 1928, he kept his part of the bargain.

At the end of 1928, the BBC decided that Baird television had "not yet reached a practical stage," an announcement that was received with amazement by many. The editor of Amateur Wireless responded with an article that stated; 'We say most definitely that the Baird system does justify a broadcast trial.' The controversy eventually led to a breach between Baird's associates and the British Broadcasting Corporation, at the head of which was Sir John Reith, a fellow student of Baird in earlier days. Were there some personal differences between the two fellow countrymen? Was Reith himself responsible for holding back the development of television?