The History of Television in Ireland

There was a suspicion about the type of 'British' broadcasting viewers could expect and the negative influence it would undoubtedly have on the Irish.

It was in 1949 that television was first received in Ireland when, on 17 December, the BBC began transmitting from a new 887 foot mast at Sutton Coldfield in Birmingham. The powerful transmitter meant that those living along parts of the east coast of Ireland were able to receive the signal. But it wasn't until 1953 that broadcasting began on the island itself with the launch of BBC Ireland. Even then there was a suspicion by many about the type of 'British' broadcasting viewers could expect and the negative influence it would undoubtedly have on the Irish people. So, in hindsight, when it was suggested that Ireland have its own public service broadcasting system, a system that could come under closer control and regulation, it may be seen as odd that the Government dismissed the idea, calling television nothing more than a 'luxury service' that was largely unwanted by the population. Ireland had very little interest in developing a home-grown service although it did, rather begrudgingly, allow the formation of a research committee. But as we will explore in this article, there was good reason for suspicion. For many, the objections to television echoed those that were broached when radio broadcasting was suggested in the 1920s. However, television was in for a far bumpier ride.

When the BBC began transmitting in Britain in 1922, Ireland was in the midst of a bloody civil war. It wasn't until hostilities subsided that the question of sound broadcasting was even considered. When the white paper for the Irish Broadcasting Company was eventually put before the Dáil Éireann (the Assembly of Ireland), it was rejected. This rejection was due, in no small part, to the fact that a number of the companies that had proposed to form the broadcasting service were manufacturers of radio equipment-and therefore were only in it to exploit it as a profit-making enterprise. Furthermore, aware of the huge influence that radio could have on a political, social and cultural level, members of the Dáil demanded that the state have strict control over any national radio service and were concerned that any lack of control would allow interested parties to use the medium to further their own political agendas. Eventually it was agreed that the Post Office would be responsible for running the new state-owned and operated radio service which would be run from licence fees, taxes on the import of receivers, and a small amount of advertising. Regular radio broadcasting in Ireland began on 1 January 1926. But the state-owned Radio Éireann began broadcasting in 1932, ten years after BBC radio had begun. And it proved to be uninspiring and largely unsupported by the government. The only thing that seemed of interest was the amount of taxes collected from the importation of receivers. When the Department of Finance realised just how lucrative this was it took away the job of collecting the tax from the Post Office and collected the tax itself. As a result of this loss of revenue the radio station suffered even more.

Leon O'Broin

And so, when in 1950, Leon O'Broin, the secretary at the Department of Post and Telegraphs, established a committee on Irish television, many of the old arguments and objections that had held back radio for so long were raised yet again. O'Broin had written to the Department of Finance in January 1950 requesting £180 to purchase a television receiver to enable his newly formed Television Committee to observe broadcasts coming from Britain. He reasoned that as public service television in Ireland was inevitable, and as the BBC was scheduled to open a transmitter in Northern Ireland in 1951, it was only right that the country should have its own broadcaster, sooner rather than later. The DoF countered with a dismissive internal memo that read: "…(it would be) ridiculous to think of a Television Service in a country which has manifested no interest in it and whose people would probably be opposed to the spending of considerable sums of money on such a luxury." The memo finished "Television is a long way off here." But O'Broin persevered. "Speaking quite frankly", he told Finance "there is no use sticking our heads in the sand and pretending that we shall escape the storm by simply saying and doing nothing." Reluctantly, Finance gave O'Broin his £180. The relationship between O'Broin's department and Finance continued to be a hostile one. O'Broin directly approached the Taoiseach (the head of government or Prime Minister of Ireland) and Cabinet, asking for further research funds, deliberately bypassing Finance who he knew would raise objections. When Finance discovered this they wrote to the Taoiseach objecting to any Government involvement in television. But once again O'Broin was successful in his request.

O'Broin set out a number of different possibilities for ownership and control of an Irish TV network which he said could either be (a) owned directly by the state, (b) owned by a public corporation, (c) owned by private enterprise, or (d) using a combination where transmitters would be owned by the state and content would be provided by private enterprises. The Committee strongly endorsed the foundation of a public service as opposed to a private one, but realised the financial difficulties inherent in establishing one. But it also suggested that a Government owned public service-that accepted advertising, was also an option.

As the debate continued the political landscape in Ireland was set to change. With a general election looming in May 1954 the question of television was put firmly on hold. By July 1955, in spite of a change of government little had changed with regards to the further development of television, although that particular month saw the erection of a new BBC transmitter on top of Divis Mountain, outside Belfast, greatly increasing the range of the BBC in Ireland. The result was an increase in public demand for television sets. There was now an estimated 7,000 sets in use. In March 1956, the Television Committee submitted a new report on the delivery of a home-grown television service. The report outlined why this was now of urgent importance - stating that the BBC programmes were in the most part wholly unsuitable: "Some are brazen, some "frank" in sex matters, some merely inspired by the desire to exalt the British Royal Family and the British way of life. The last element naturally runs through a wide variety of programmes (with) emphasis on the British way of life, the British view of world affairs, and the British achievements." But the government stood firm. Whilst stating they were in favour of a public service television, they stated quite categorically that "the establishment of such a service would involve expenditure beyond the resources available to the state" and furthermore would be undesirable because it would encourage imports of luxury goods "to the detriment of our national economy."

With an Irish run television service now firmly denied it would be another year before the subject was raised again, and it needed a change of government to kick-start it. In March 1957, Ireland's coalition government collapsed when Clann na Poblachta (an Irish republican party founded by former Irish Republican Army Chief of Staff Seán MacBride in 1946) withdrew its support for Fine Gael (meaning Family or Tribe of the Irish). In the election that followed, Fianna Fail, a party seen as to the left of Fine Gael and to the right of Sinn Féin and the Labour Party, won a majority. In the summer of that year both the Irish and British press published specific details of private companies that had approached the government with proposals for setting up a television service. The revelations once more opened the debate on the structure of such a service. In October the Cabinet announced that it had studied all the proposals and had come to a decision. It was their position that Irish television should be "established as early as practicable." A committee was formed in October to determine the most effective way of making this happen. In October, Neil Blaney, the Minister for Posts and Telegraphs issued a public statement inviting proposals from companies interested in broadcasting an Irish television service. That service would be largely commercial with private interests.

In order to consider all the different proposals, the government created the Television Commission; its first meeting taking place on 9 April 1958. Eventually a shortlist of consortiums was presented. Three made the commission's shortlist, 8 others were dismissed out of hand. When the full report was submitted to government in May 1959, there was much confusion and consternation. Of the three, the report failed to make any recommendation on who the preferred candidate was, suggesting that the government should enter into negotiations with all of them. At this point something unexpected happened. The DoF, which up until that time was set firmly against the introduction of an Irish television service, did an about-turn. In a memo sent to Government it was stated that: "If a television service were to be provided, the Minister of Finance would be prepared to consider an arrangement under which the capital would be provided by the Government on a profit-earning basis. The Minister understands that the Minister for posts and Telegraphs is strongly in favour of the recommendations made…that the Television Authority, which would be a state-sponsored body, would provide and operate the service, financed by licence fees and advertising revenue." 6 years after it had first been proposed as an option in the Television Committee's 1953 report, the government adopted the suggestion for a dual commercial and state-financed public service broadcaster.

On 13 July 1959, a final decision was made. Leon O'Broin's department would oversee the drafting of the legislation needed to establish the television authority, which became the Broadcasting Authority Act 1960. Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) was established on 1 June 1960 (as Radio Éireann). It's first chairman was Eamonn Andrews, who chaired the authority until 1964, overseeing the introduction of State television to Ireland and establishing the Irish State broadcaster as an independent semi-state body (the name of the authority was changed to Radio Telefís Éireann by the Broadcasting Authority (Amendment) Act 1966, and both the radio and television services became known as RTÉ in that year).

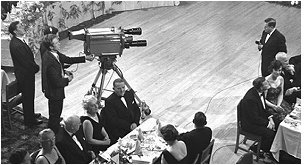

Telefís Éireann began broadcasting at 19:00 hours on New Year's Eve, 1961. The channel was launched with an opening address by the then President and former Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera. There were messages from Cardinal d'Alton and Seán Lemass who had succeeded de Valera at the head of government. There then followed a live concert from Dublin. The next programme, a light entertainment show that saw in the New Year, was hosted by Eamonn Andrews who introduced a number of guests. In the ensuing years television had a huge influence on social structure and attitudes in Ireland, in many ways that had been predicted by those who had originally stood so firmly against it, although perhaps not necessarily in the ways it had been anticipated. Months before its launch The Catholic Truth Society had warned about the dangers of television: "More souls may be taken away from Christ through the Gospel of pleasure they absorb from television, than if the Antichrist would start an open bloody persecution in our country." Even Éamon de Valera's inaugural speech on opening night had solemnly warned about television's "nuclear" power to destroy morals. "Like atomic energy", he said it could be "used either for good or bad." It could either impart knowledge and build the character of a whole people or it could "lead through demoralisation to decadence and dissolution".

Within a year television in Ireland was rocked by its first sex scandal when the station withdrew a sketch-drawing advert for Bri-Nylon underwear. RTÉ conceded that the cartoon of Anthony and Cleopatra was "lewd and lascivious". The entertainment show The Late Late Show, which began in July 1962 and is still broadcasting today, also courted controversy in 1966 when presenter Gay Byrne asked a female contestant, during a Mr & Mrs sketch, about the colour of her nightie. The following day a Bishop called on "all decent Irish Catholics" to protest - but his request went largely ignored. Ireland's top soap of the 1960s and 1970s, The Riordans, tackled birth outside of marriage, but took caution by making the culprit an English niece of the local Protestant bigwigs. But when writer Wesley Burroughs developed a plotline which hinted that Maggie Riordan was pregnant outside of marriage, he had gone too far. Burroughs received a dressing down from RTÉ authorities and had to go through medical books to find an illness that would innocently explain away Maggie's expanding midriff.

Dr Helena Sheehan, Professor Emerita at Dublin City University says that television was inevitably an instrument of modernisation: "Television did much more than reflect the liberalisation of Irish society. It also did a great deal to contribute actively to its liberalisation". Tom Englis of the School of Sociology in Dublin also believes that the impact of television was an integral part of the modernisation of Irish society in the 1960s. "In terms of knowledge and understanding of the world and in terms of people interpreting and understanding themselves, the machine that brought most change to Irish life during the last half of the twentieth century was the television. It was then that Ireland began to open up to the outside world. The pursuit of economic growth, the increase in international trade and the gradual dismantling of the walls of censorship meant that global flows of goods, technology and ideas began to seep into Irish culture and society."

Next Article: A Short History of the Television Play

Article

This article, 2014. Links: Sucked Into The Tube RTÉ Television (Wikipedia) RTÉ Homepage | Further reading: Irish Television - The Political and Social Origins by Robert J. Savage. ISBN 1-85918-101-5 | A Great Feast of Light by John Doyle. ISBN 1-84513-259-9 | Special thanks to Sue Murray at RTÉ

Ulster Television

The governing body of the Independent Television network, the Independent Television Authority, first advertised the franchise for Northern Ireland in September 1958. Two consortia applied for the franchise but the ITA eventually persuaded both applicants to merge their bids. The group, under the name Ulster Television Limited, set out their plans for broadcasting. Ulster Television went on air at 4.45 pm on Saturday 31 October 1959.

At launch, Ulster Television employed a staff of 100 people, and programmes would only be available to viewers located within range of the Black Mountain transmitter near Belfast. Coverage of UTV only spread to Western areas of Northern Ireland when the Strabane transmitter opened as late as February 1963, and a colour service wasn't launched until September 1970 with the opening of the UHF transmitter Divis.

UTV became the last ITV network station to start broadcasting for 24 hours a day in October 1988.

In May 2006 Ulster Television plc became UTV plc and in 2007 that name was changed to UTV Media PLC. In 2016 UTV sold its franchise to ITV plc.