John Cura's Telesnaps

By the 1950s Cura had built himself quite a lucrative business, and it began to cause unrest amongst the hierarchy of the BBC

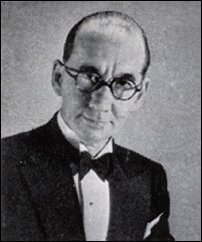

Many fans of the lost 1960s episodes of Doctor Who will be familiar, and not in the very least ungrateful, for the work of a small bespectacled man who in 1947 developed a unique technique of preserving still images of 'live' TV shows. For had it not been for John Cura, there would be very little evidence left of wiped episodes of the cult science fiction series. Unfortunately, there is very little evidence left of Cura's earlier work, but what is left is worthy of special mention as it is another sorry tale of how a piece of British television history has been lost forever.

On 7 June 1946 after almost seven years of being off-the-air the BBC resumed its television service to the British people following the Second World War. Actually, it's fairer to say that it resumed its service to Londoners only, because it wasn't until 1949 that transmissions reached beyond the capital. Television technology was still very much in its infancy and apart from 'bought in' feature films all transmissions went out live. Experiments in tele-recording produced crude copies of live shows and the results of video-tape, still in the early stages of development was not only unreliable but also an expensive alternative. Therefore, any 'transmission', such as a play, that required a repeat viewing had to be performed again on another night by the same cast of actors. So very little exists today of British television's formative years.

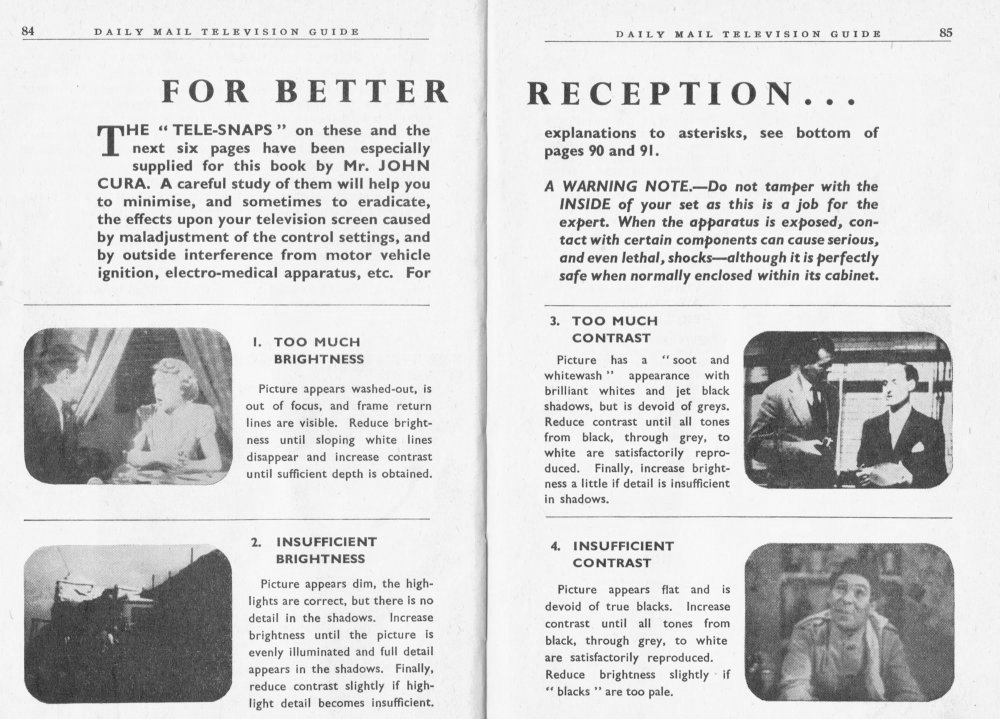

But in South London, one man was experimenting with a method of capturing those transmitted historical images and preserving them for prosperity. Alberto Giovanni Curà was born on 9 April 1902 to a father of Italian descent and a British mother. By 1947, at the age of 45, Alberto (who had by now adopted the more English sounding name of John), had developed his own camera to capture images off a TV screen as they were being transmitted. Although they were taken from the low-tech 405-line images these Tele-Snaps, as Cura dubbed them, soon became much sought after by newspapers and magazines and many publishers beat a path to his home at 176a Northcote Road, Clapham.

By October of that year, Cura felt confident enough in having perfected his photographic method, to write a letter to the BBC requesting use of the photographs for commercial exploitation. The letter caused great consternation within the BBC as nobody knew exactly what the legal position was. To this day, the BBC still have on file a whole load of internal memos from their legal department to none other than the Deputy Director-General who finally replied that Cura was given clearance to take these photographs only at the request of the stars themselves and only for the purpose of selling the pictures back to them. There was also a request not to "make any references to the Corporation on or in connection with the photographs."

By the 1950s Cura had built himself quite a lucrative business, and it began to cause unrest amongst the hierarchy of the BBC as Cecil Madden pointed out in an internal memo: 'I don’t know if you have heard of the activities of this man, but I gather he photographs almost everything that appears on the Television screen, and then writes to everybody suggesting they buy copies at thumbnail sizes, which can be enlarged. Cura must be making a splendid lot out of it. He has discovered a business with almost no overheads and an inexhaustible supply of buyers!'

By this time, Cura was both producing and selling his "inexhaustible supply" of pictures to newspapers and magazines around the world. When the Oxford boat crew sank in the 1951 university boat race Cura's Tele-Snaps were the first pictures to be published of the event. And by now, even BBC producers were becoming aware of the benefits of having Cura's photographs as producer Mary Burrell-Davis recalled: ‘The staff found it a very useful service. If you were doing a live broadcast you didn’t really know what the result was, but you could sit down afterwards, look at the Tele-Snaps and think “That was a good camera position” or “That was a rotten camera position.”

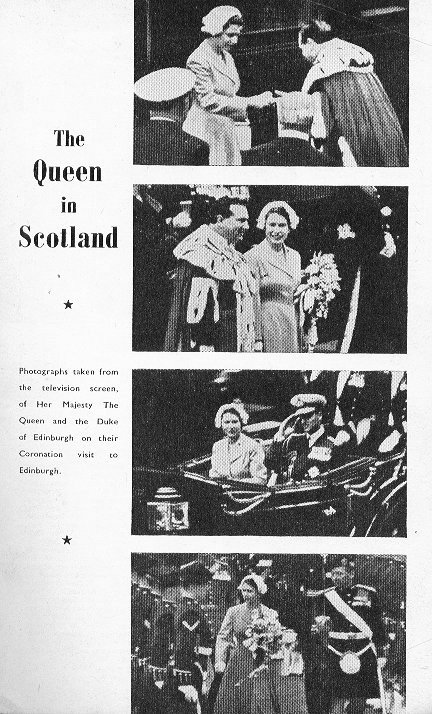

During the 1950s Tele-Snaps went from strength to strength and were even in demand from television manufacturers to be reproduced in advertising campaigns. Even the BBC's position mellowed somewhat with both the Radio Times and The Listener publishing Cura's photographs. In 1953, some of Cura's Coronation images were mounted in a commemorative album presented by the BBC to the Queen. The arrival of Britain's second TV channel further increased Cura's workload as now ITV wanted his talents, too. On BBC he 'snapped' Z Cars, Compact, A For Andromeda and in particular Doctor Who, which proved its worth many years later when the BBC dumped over 100 episodes, leaving Cura's pictures the only reference of scene by scene breakdowns. But by the mid 1960s technology began to catch up with Cura. With TV programmes now being pre-recorded on film or video, the Corporation began to re-evaluate the worthiness of the Tele-Snaps, which they were spending around £1300 a year on.

John Cura passed away following colon cancer on 21 April 1969, aged 67. He left behind thousands of photographs in his garage at home. A veritable treasure-trove of British televisual history. His wife, Emily, contacted the BBC and asked them if they wanted the pictures, to which she allegedly got the response 'We’re moving forward, Mrs Cura, not backwards.' She was so incensed and upset by their response that she destroyed every last one of them.

Only a fraction of John Cura's work has survived today. Much of his Doctor Who work survives and the rest are in the private hands of artistes and producers for whom he had worked. The BFI have some, and so do the BBC. Some others, like the ones above and below from the Daily Mail Television Guide (circa 1953), may be found in old TV books and annuals.

Laurence Marcus