Z Cars - Year One

Peter Lewis' contemporary article published in Contrast - The Television Quarterly - Summer 1962 looks at the series that broke new ground in police procedurals. Loved by the public but despised by many senior police officers, Z Cars was the first character driven police drama that reflected the harsh realism of policing in a provincial town in the North of England that, according to Lewis, 'made all its rivals obsolete.'

The creation of Troy Kennedy Martin, the series ran for over 800 episodes from January 1962 to September 1978. But by the end of the first year, Kennedy Martin was already becoming disillusioned with its success, convinced that the demand for more episodes (extended from the projected 13 episodes to 31) would hold back the development of the characters that he had painstakingly created.

Z Cars by Peter Lewis

‘The programme showed the police in a pretty poor light - one officer a wife-beater, another gambling madly on horses. We know policemen are human but this was ridiculous. At a time when we are trying to raise the status of the police in the public eye this nonsense could do harm.’

That was the reaction of Sergeant Charles White, chairman of the Police Federation, to the first episode of Z Cars. He was not alone. Unnamed senior officers were much quoted in the next few days: ‘The programme set our relationship with the public back 20 years .... This isn`t the kind of picture of the Force that is going to get us the recruits we need .... Officers were shown eating disgustingly.’ The Chief Constable of Lancashire paid a much publicized visit to Stuart Hood of the BBC, and the credit thanking the Lancashire County Police for their co-operation was quietly dropped.

The tone of these complaints was interesting. ‘Picture of the Force’. ‘Status in the public eye’. ‘Eating disgustingly’. So deeply has the public relations habit of thought seeped into ordinary men. ‘Constable! Talking with your mouth full! I know you’re human but this is ridiculous!’ The Police Federation chairman said the programme was ‘nowhere near the class of Dixon of Dock Green. Class was the word he used, and it wasn’t surprising.

Another Chief Constable (Bedfordshire) restored a note of realism. ‘A policeman’s wife with a black eye,’ he asked mildly. ‘Why not? There must be some policemen who occasionally black their wives’ eyes.’ As for the effect on the recruiting figures, one wonders what sort of recruits they think they’re after. A whole division of Jack Warners?

All this anguished disapproval must have been very heartening for the creative men concerned.

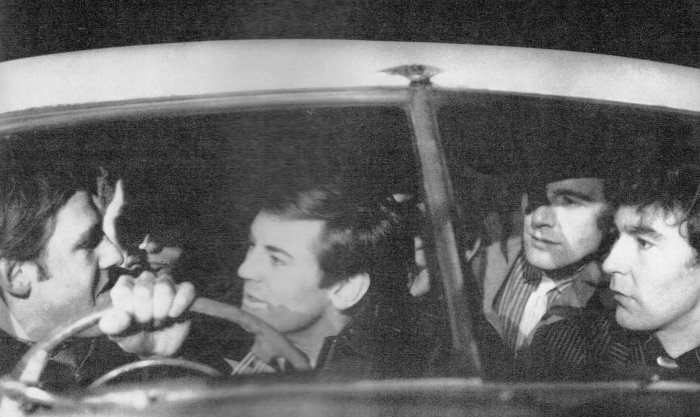

This close-up of four delinquents, led by Anthony Booth (from the episode 'Threats and Menaces') catches the realism of production.

What precisely had been achieved? Basically it was another cops-and-robbers series, with a high degree of technical polish, provided at the fairly high cost of up to £3,000 an episode. Next, it had a new setting- not merely Lancashire, but a new town near Liverpool, the sort of community without landmarks which has not been explored before. Lastly, and by far the most important, it had characters who grew out of the background with a sharp taste of authenticity. They were not policemen fitted out with characters, along with the uniforms from the wardrobe. They were people who happened to be policemen; people conditioned by everyday contact with violence. They exhibited the hardness, indifference and contempt that goes with the profession of beating professional crooks at the game, as well as the usual human complement of ambition, envy, malice, laziness, courage, kindness and bloody-mindedness. There can be little doubt that the policed public saw something here that it recognized as true and did not altogether dislike, however much it pained the Police Federation. The audience climbed from 9 million to 14 million in eight weeks.

Troy Kennedy Martin

Z Cars came about because Troy Kennedy Martin had mumps. Sitting in bed, listening to VHF radio, he idly began monitoring the police calls. By the time he had lost the swelling he had germinated the idea for the series. The next stage occurred when Elwyn Jones, assistant head of BBC drama, went up to Liverpool to show Colin Morris’s celebrated feature Who, Me? to a group of Lancashire detectives. He asked whether they used car patrols and what they were called. The answer was ‘Crime Cars’ - which sounded too readymade a title to be true - but they were also called ‘Z Cars’. BBC relations with the Lancashire County Police, the premier provincial force, were already very close, thanks to Who, Me? and the series that followed it called Jacks and Knaves. Kennedy Martin was sent up to reconnoitre and came back with an excited report on the terrain and the possibilities. In the autumn he went back with co-writer Allan Prior to live among the police and write the first scripts. With the brilliantly observed opening episode he created a living, Z Car world, complete with the four constables who carry the series, their superiors, their home country and their attitude towards it.

From the start great emphasis was placed on the documentary approach. Of the first 12 scripts, three were based directly on true happenings and the remainder were improvised from situations typical of crime car work in that police division of Lancashire. A lot of trouble was taken to find out such things as where safe-blowers get gelignite and how they hide it, how sheep stealers work, what brings the police out on typical Friday nights, just which officers take charge of operations in a jail break.

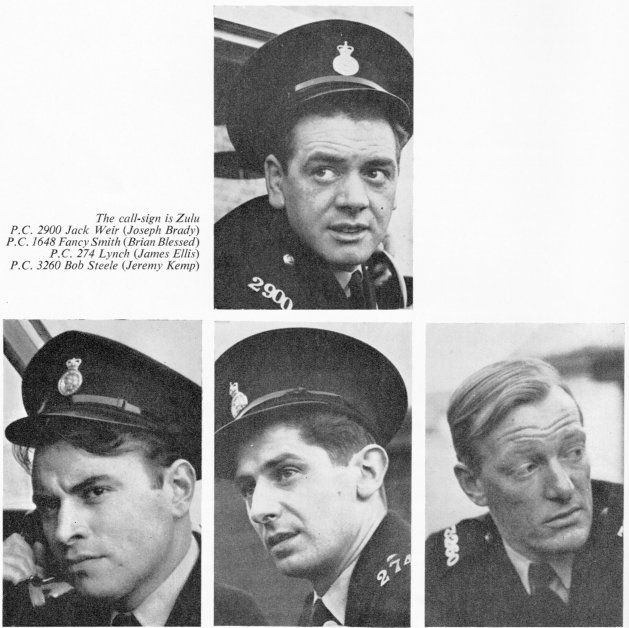

The casting was done by John McGrath, the first producer to handle the series. He looked for a particular kind of actor, of whom honesty was the key requirement. None of them had name value. They were sent to Lancashire to do some preliminary filming, went out in the crime cars, went to the policemen’s homes and got to know them. ‘Before we began rehearsals,’ says McGrath, ‘I spent a clear week with them discussing the complete social background of every character - age, parentage, why they were in the police force, what they wanted out of it. We filled it all in, in great detail. Not one of these blokes would say a line without knowing why he was saying it.’ This kind of approach, still rare in the commercial theatre, was practically unknown in television. One result is that the actors are happy. They have the liberty to create their own characters. If a line of dialogue or an action feels wrong their objections are listened to. This common regard for truth has helped them to develop what one of them called ‘second sight’ in performance, akin to playing like an orchestra for the sake of the total result, not the individual parts. The documentary purism of approach extends to allowing no billing or cast list in the Radio Times.

The sheer technical feat of producing a Z Cars episode makes this closeness of mutual understanding absolutely essential. It is done live. Only the scenes showing open streets are filmed. The Z car, suitably soiled, stands on wooden rollers for easy manoeuvring in front of back projection screens that produce the 60 m.p.h. illusions. The studio is littered with 14 or 15 different sets each week. Five cameras travel the floor ceaselessly. There are something like 250 changes of shot in each episode - an average of five a minute. The actor’s worst problem is to remember which scene he is in. All this is rehearsed in two days of studio time. Each week they shoot the equivalent of a fast-moving feature film in fifty minutes flat with no retakes. In the control room every Tuesday night they do what might take a film studio cutting room at least a week. That is a measure of the technical advance that Z Cars represents.

But of course no amount of care in research and expertness of technique in themselves make a series original, exciting or memorable. It is the writer that counts; the quality of his imagination, his sympathy with his subject and whether he has anything to say of a universal human kind. The basic difference between Z Cars and all other crime series is that it was the creation of one writer, Troy Kennedy Martin. He is 30, a Dubliner, alert and feline of movement with an expression of permanent, slight amusement. One of his main fertilizing experiences was his National Service in Cyprus during the EOKA emergency. This bore fruit in a documentary, Incident at Echo 6, and a play called The Interrogator. He has written a novel and he wrote the Storyboard series. Z Cars was completely fresh ground. As a natural fiction writer he found himself forced into what the BBC regarded as primarily a job of documentary writing, under the control of a group producer, Robert Barr, with a distinguished documentary reputation. The resulting friction between them made the series what it is. Both men, with a rueful regard for each other, are prepared to admit that it wouldn’t have been as good without the fighting. ‘One of the qualities of Z Cars,’ says Barr, ‘comes from a constant war between me, who wants it to be documentary, and Troy, who wants to write fiction.'

At their best the scripts (of the first 13, 6 were by Martin, 5 by Allan Prior, 2 by Robert Barr, and Michael Ashe) have undercurrents moving beneath the surface. There is a stream of unstated protest- against the ugliness of life in New Town, against materialistic apathy, against the kind of people who gather round the scene of a crime to stare hungrily. (The characters who come out of Z Cars worst are usually not the crooks but the general public.) There is another stream, one of morality, exhibited in the tough, impatient professionalism of the police, wearied by the nastiness of human nature and wanting their tea. What emerges is a kind of dry-eyed lament for life as it is messily lived in Britain in affluent 1962.

Here is an illustration - a road accident on a drunken Friday night: a boy motor cyclist dying, the girl on the pillion dead, the usual unhelpful crowd assembled. A single policeman, Steele, is holding the boy.

Steele: Hey, you! Find the telephone on the front seat, press the little tit on its backside and tell Headquarters what’s happening. Ask them where the hell the ambulance is.

Farmer: I’ve never worked one before.

Steele: Then try! It won’t bite you.

Female: He’s got a hole in his head. ’e won’t last. I saw it - it were

the church railings.

Youth: Daddy - daddy . . .

Steele: Easy, son, it’s only a scratch. Bring that blanket from the

back of the car.

Female: You’ve got blood on your uniform.

Steele: Get that bloody blanket!

Driver: I don’t know what happened - there was this motor-cyclist - flying through the air, he was, four feet off the ground in front of my headlamps. They won’t prosecute, will they? l mean there was hardly a bump, were there?

Farmer (in car): The policeman wants to know when the ambulance is coming.

Girl’s voice: Tell him ambulance and traffic patrol are coming immediately. Now please remove your hand from the button as we have other calls to deal with.

Lynch, arriving: There you are . _ .

Steele: Get that feller into crime car, he’s drunk and he were the cause of it.

Driver: I refuse to be examined without my own doctor being present and he’s on holiday in the Canaries.

Lynch: Get in there and shut it.

Driver: You’re like the ruddy Gestapo. This isn’t a police state.

Lynch: No-one’s had any tea through you, now sit quiet.

Steele: The ambulance?

Patrol woman: It’s coming. Can l just have a look at him?

Steele: He was talking quite clearly a minute ago - but he’s got a hole in his head. (Slightly hysterical) I’m keeping him out of the rain until it comes.

Patrol woman: He’s dead.

Sergeant, (putting down ’phone in police station): That accident. It’s a double fatal. Motor cyclist’s pulled the short straws. Get an accident sheet, lad, it means paper work.

There is an after-taste in these lines, a feeling for the wasteful chaos of life. A few minutes after the constables have broken the news of death to the boy’s mother they are out picking up a couple of drunks who have broken a window. Among the debris of Friday night, tragedy flies by and people are too busy to take it in. We have not been given this kind of depth and counterpoint before. Certainly not in No Hiding Place or Dixon or the glossies - Ward 10, Harpers and Compact. The concern behind it is Troy Kennedy Martin’s. He thinks series are important and he approaches them with the feelings of a playwright, not of a hack. ‘The main purpose if a series is to hold a mirror up to English life as it is at the moment. This is something which television series have obviously failed to do. The pictures most of them have drawn have been patently untrue. I also wanted to break down the dominance of the story line and put in its place character and dialogue. I wanted to reassert the fundamental values of life. Death, for instance. We planned to have no more than one murder in the first 13 episodes and when death occurred it was to be, as it should be, terrifying. Ironically, Z Cars gets a reputation for being violent because a man was pushed into a lavatory and thumped, once. In many crime series it is quite accepted that a dozen people should be shot in the belly.

‘These ideas were there before I saw Lancashire, I already wanted to write about the North of England. I felt it was a bit of a promised land. When I got there it frightened me. It was alien to me. I hated it at the beginning and one is more sharply aware of things one hates. In the new town one felt the rawness of the Wild West. Before the station was built the police had a Nissen hut. The atmosphere was as tense, tough, taut as anything in Cyprus. One of the constables was helping organize a Boy Scout jumble sale, and the situation was such that the Scouts were guarding it all night.

‘I hated the appalling lack of taste everywhere. You would sit in a hotel and count the clashing colours of the chairs, the carpets, the contemporary wallpaper, the contemporary light fittings. But I loved those police officers, those warm, huge men with their boots and their tremendous solidity. They had a tradition, one that is vanishing from Britain as the South, and America, takes over. It is a man’s country all right, with fights in the pubs and husbands hitting wives. There’s a hard brand of humour. The women have a self contained independence. Of course, all this is in the main-stream of the developments in the novel and the theatre. It’s Room at the Top and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning country, but television hadn`t caught up with it.’

He is not very interested in the mechanics of the plots. He cares much more about showing two half-canned detectives being taken home after a hot-pot supper, or the way Steele, the tough policeman, is treated by his wife - indeed, in the way anybody is treated by anybody else. All these things, of course, are inessential to the plot. That’s why they are usually left out of other series.

‘I got my characters from the police. I drew a lot on what I saw -the Sergeant Watts, the Inspector Barlows. Then John McGrath got exceptionally strong actors to create them. I was very influenced by the new school of actors, the Finney - O’Toole type, who already existed, waiting to be used.’

‘We started with character, not plot. That was the fundamental difference of attitude. Action must spring from character. But now,’ he said, coming to it, ‘What they want are stories. They think once you’ve got a story you’re half-way home. Character is being squeezed out. Partly by the sheer pressure of getting the episodes out. Partly by the influence of the police scrutiny of the scripts.’

As any ‘authorized biography’ proves, it is almost always fatal to let the subject see what you are writing. The reason for wanting police scrutiny was to get police procedure right. But of course it didn’t stop at procedure. The police tended to assume the mantle of literary critics.

‘The word “the” is missing from the officer’s remarks.’ A good deal of rather amusing confusion set in. Swearing was pruned. The BBC mind soon substituted ‘ruddy` for ‘bloody’ but then the police pointed out that their officers didn’t bloody well say ruddy. There was one hilarious final rehearsal when agonized BBC superiors tried to lay down the precise degree of drunkenness which was permissible in the pair of detectives who had been celebrating. With exquisite subtlety it was agreed that they could be ‘happy’ but not ‘merry’.

More important than these verbal refinements was the whittling away of class attitudes. The crime patrol began with a firmly working class crew - superior working class, but working class. There was soon pressure to make them £1,000-a-year men. One week Sergeant Watt got a shiny new raincoat. Another, Janey, the policeman’s wife, got a snazzy new cooker to replace the old stove. All small things in themselves, but the accumulated effect has been to blur the sharp outlines with which the series began. In spite of the efforts of the actors, the police have become less interesting as people, not more, as the series has worn on.

But the real danger to Z Cars is its sheer success. As soon as the BBC realized it was on a winner the run of the series was extended from the projected 13 episodes to 31. There is to be a second series after a six-week break. This was a hard-faced commercial decision and surely not a wise one. No writer can produce that many episodes on the run. There are now eight writers engaged on the series, which means that it is out of the control of its creator. There are already signs that the coinage of the writing is being debased for the sake of productivity. On top of that the production problems are formidable. You cannot use the same director two weeks running because next week’s episode must go into rehearsal this week. Key actors alternate between episodes. What playwright has to write Act Three, Scene Two without knowing what is in Act Three, Scene One . . . and have to do without some of his main characters in every scene he writes . . . and not even know which characters will be absent when he is writing it?

And this raises the key question about series. Up till now the series has been to the play what the strip cartoon is to the novel. But ideally a series could have the development of a play spread out over its episodes. Its characters could grow as people grow in life. Z Cars began with plenty of strong, well-differentiated characters. It gave them the background and the elbow room to develop. But the development has not occurred. Could it?

Troy Kennedy Martin thinks it should but doesn’t think it will. ‘It’s like a meat factory,’ he said. ‘The organization isn’t there to allow character development. You would need a far more closely knit team of writers and directors bound together with a common attitude and enthusiasm. It calls for living together, living for the series, which is the sort of thing that has never happened in television. A series is a living thing, always twisting and turning. But if they insist on this sameness week after week then the characters tend to become caricatures of themselves. After a time you just get hollowness and nothing.’

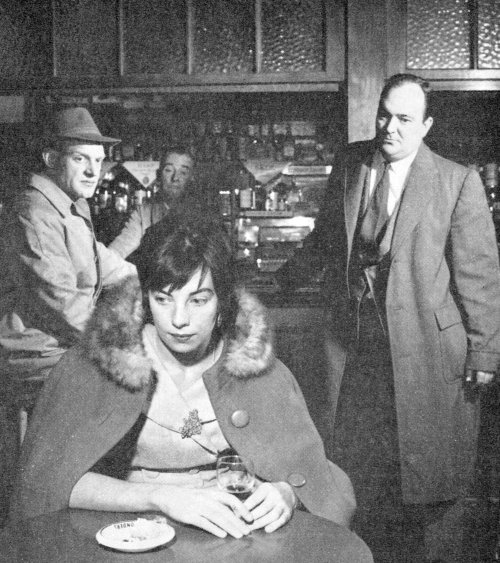

Z Cars episode 'The Big Catch' with Frank Windsor as Sergeant Watt, Morris Parsons, Patricia Healey and Stratford Johns as Chief Inspector Barlow

These are the usual frustrations of a creative writer shackled to a mass medium with an insatiable hunger for copy. Perhaps this writer is being unduly pessimistic when he says there has been a 30 per cent loss of his intentions in the series as it has emerged on the screen. Perhaps the failure has been partly his own. Nevertheless his words have a gloomy and depressing familiarity. ‘lf they insist on this sameness . . .’ And of course they do insist on sameness and they always will. The philosophy is: when you’ve got a winning formula, stick to it. Robert Barr put it revealingly: ‘As soon as a series becomes successful you’re on the tail of a comet. You can’t start destroying the characters you have created - because now they belong to the public.’

This is what might be called Sharples’ Disease and there’s no doubt it is real. People like what they know, they like their expectations to be fulfilled, they get cross and feel let down if characters don’t behave predictably; life doesn’t perform to a formula, and the more you insist on a formula in fiction, the less you reflect life. Z Cars has enough truth and honesty in it to make it the most hopeful thing that has happened in the series’ world since television started. It has already made all its rivals obsolete. Can it, or can any series to come, go on from there and take the next precarious step towards the level of art?

Peter Lewis – Writing for Contrast – The Television Quarterly (Summer 1962).

About Peter Lewis

Peter Lewis was a celebrated journalist who excelled as reporter, feature writer, award-winning foreign correspondent, star interviewer, theatre critic, literary editor and book reviewer. An accomplished artist and pianist, Lewis wrote comedy sketches for That Was The Week That Was, The Two Ronnies, Marty Feldman and the original TV series That's Your Funeral, which he later developed into a feature film.

He was born in 1928 and educated at Stowe School and Oxford University. His journalistic career began in local newspapers before he moved to Fleet Street as a sub-editor, checking copy and writing headlines on the Daily Express in the mid-Fifties, before moving on to the Daily Mail where he had a long and distinguished career. When he passed away in 2016, the Mail said this of him in tribute: His reviews, which enriched the books pages for so many years, were masterpieces of concision, depth and wit.