The Armchair Theatre Effect

"Television dramas were usually adaptations of stage plays, and invariably about upper classes. I said 'Damn the upper-classes -they don't even own televisions!'"

When commercial television began in September 1955 ATV tried to compete on the same level as the BBC's drama output by offering its viewers fragments of Oscar Wilde and Noel Coward (on Rediffusion's opening night) and the 30-minute Theatre Royal, the first ITV play series which began broadcasting on 25th September, 1955, with a televised Dickens episode, Bardell v Pickwick. The series was produced by Harry Alan Towers' independent Towers of London Productions company for ITC. Also on offer was London Playhouse a series which drew on the standard West End fare that was on offer at the time.

Pioneered by Howard Thomas and launched by ABC television in 1956 with the play The Outsider starring David Kossoff, Armchair Theatre would have a more lasting impact. Thomas had previously been a journalist, an advertising man and a BBC producer (he created The Brains Trust), and came to television following a long period in charge of documentary films for Associated British Pathe, where he produced the Coronation film Elizabeth is Queen. Dennis Vance produced Armchair Theatre for two years. Born in Birkenhead, Cheshire, Vance began his career as an actor in the late 1940s, before switching to become a producer with the BBC in the early 1950s. He left the Corporation in 1955 to produce The Adventures of the Scarlet Pimpernel (1955-56) for Towers of London Productions, before becoming the first Head of Drama at Associated British Corporation (ABC). That first Armchair Theatre presentation played to an audience of 390,000 homes (audience figures were measured in homes rather than viewers in the 1950s. The 'average viewers' was regarded as 2.4 per home. About 51% of homes were equipped to receive ITV at that time).

Leonard White, later to become producer of Armchair Theatre says that it was the second presentation in the first series that started to establish the programme's mainstream commitment to commissioning original TV drama scripts with a double-bill of new works. The Handshake starring Rosalie Crutchley, Anton Diffring and Billie Whitelaw, was written by Peter Key and directed by Stuart Latham. The same cast acted in Duncan Greenwood's Bid for Fame. In that first season 41 single-play productions were made.

The Armchair Theatre series began to gain ground in 1958 with the arrival of Canadian producer Sydney Newman and his commissioning of scripts from some of the most promising young talents in the country. Newman took over from Vance (following the latter's decision to go free-lance) as Drama Supervisor for ABC Television in April 1958. In Autumn of that year he embarked on a plan to make Armchair Theatre as far as possible an all-British programme with every play specially written for the series.

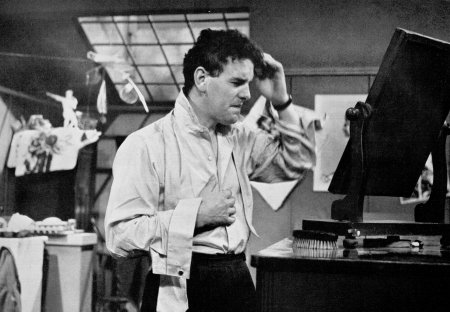

Sydney Newman (at desk) discussing the treatment of a play with his production staff. Verity Lambert, then a production assistant, is seated at the back.

"One must know who the audience is and, when dealing in millions, this is no easy thing. A tiny part of this mass audience who know something of the theatre, who have some knowledge of art, literature and history, would not be hard to please. When in doubt, give them Ibsen.

"From the director's point of view, Ibsen is a piece of cake. He has seen his plays performed many times before. And of course, so have the critics. But this is academic because, in fact, I have to win and hold a vast audience from every walk of life and that is a far greater and more exciting challenge. To win approval without pandering to 'idiot' level is achievement enough for any man, particularly because the majority of this audience (12 million average) would never go to the theatre even if it were gratis with free beer in the intervals.

"This vast audience may not have time to wait for Godot (no offence to Beckett), but those who would call them unintelligent on this count would be making a mistake. In fact, intelligence may have little to do with the enjoyment of a play. To satisfy the television audience may be a lot harder than to amuse pleasure-seeking and uncritical goers to a West End play. The theatre and cinema public, having made the effort to be parted with their money, become part of a captive audience. But the great TV audience is held by nothing but its own likes and dislikes. By the twist of a knob they can remove themselves from the 'theatre' without the embarrassment of a stumble over feet and a whispered "Excuse me!"

"In one of our recent plays, owing to a flubby opening, 2,700,000 people from Land's End to John O'Groats, gave us 'the bird' by flicking off within the first seven minutes. No captive audience this!"

- Sydney Newman writing in "The Armchair Theatre" 1959.

Leonard White says that the style of drama adopted by ABC was largely due to a strong Canadian influence even before Newman arrived. It started with Ted Kotcheff's arrival from CBC in Toronto. "He was a prime example of the unique style of a television drama director who had learned by doing the job at the Jarvis Street studios of CBC. One of the group who came to television unfettered by preconceptions. They regarded television as a completely new medium, special unlike any other. Whereas in the UK the general influence on television drama in the early years was from the theatre, and in the USA from cinema, in Canada there was no such strong single preconditioning." It was Kotcheff who helped Howard Thomas lure Sydney Newman from CBC.

When Newman arrived in England he immediately picked up on the 'class system' that was an inherent part of everyday life, and which also spilled over into the theatre as well as television drama. "The only legitimate theatre was of the 'anyone for tennis' variety, which, on the whole, presented a condescending view of working-class people. Television dramas were usually adaptations of stage plays, and invariably about upper classes. I said 'Damn the upper-classes -they don't even own televisions!'"

Leonard White remembers that Newman started out conventionally enough with "a few thrillers, a mystery and a medical drama. But soon the tag 'domestic drama' became a running theme - and with Ray Rigby's Boy with the Meat Axe in November 1958, Armchair Theatre began to be dubbed 'kitchen sink drama'. As television was becoming the popular form of communication so Sydney Newman set about getting the weekly drama diet to reflect day to day life of the populace and social issues of that time. Sydney honed in on naturalistic dialogue. Not for him the oh-so-English Shakespearean delivery by actors competing to out-play Gielgud or Olivier."

James Parish wrote The Great City, a story of the Blitz, for Rememberance Sunday, 1957.

Newman's approach to abandon established dramas and go for a gritty realism resulted in a series of specially commissioned plays by young playwrights such as Harold Pinter, Robert Miller, Ray Rigby and Alun Owen. "My approach," said Newman, "was to cater for the people who were buying low cost things like soap every day. The ordinary blokes the advertisers were aiming at." It was a policy that paid dividends for the both ABC TV and the viewer. The wealth of talent employed both in front and behind the cameras read like a who's who of the British entertainment industry as the weekly dramas reached the top ten ratings for 32 out of 37 weeks between 1959 and 1960. Pinter's first TV play during that period was A Night Out, and was followed that same year by Owen's Lena, O My Lena, which starred Billie Whitelaw and Peter McEnery in a terse story of a Liverpool student who falls in love with a factory worker. However, the classics were not completely abandoned and the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald (The Last Tycoon) and Oscar Wilde (The Picture of Dorian Gray) were also adapted for television. Other productions included Canadian author Mordecai Richler's own teleplay of his The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and Z Cars creator Ted Willis' Hot Summer Night.

George Cole as a bridegroom with a stag-night hangover in a 1950s Armchair Theatre production.

Newman's penchant for gritty realism, focusing on what he described as "real issues", led to the series being dubbed in class-conscious Britain as 'Armpit Theatre'. Unfortunately it is difficult to assess the quality of many of these early transmissions due to the fact that they went out live (a practice that was cruelly highlighted in 1958 when the actor Gareth Jones collapsed and died in front of the viewing audience during the play 'Underground'), and, unlike their American counterparts, these performances were not preserved on film for future generations.

By the end of the decade there was the first glimpse that the feelings of mistrust that existed in the serious theatre for television would be put aside in, initially, a grudging alliance. With the influence of television growing ever stronger and the opportunity for regular work presenting itself to many of the acting profession, it was becoming harder to ignore the pull of the new medium. However, there was still a great deal of resistance towards television, which had led many "serious professionals" to shun or simply dismiss "the box" as a passing fad. There was almost certainly something of a conspiracy amongst a select few to avoid television at all costs. What serious actor would want to stake their reputation, built up during a long and distinguished career, on one critical performance? It was a risk not considered worth taking at that time, although each of these professionals would be keeping a very cautious eye on events, acknowledging television could not be ignored for much longer, and knowing that they would eventually be drawn to it with great inevitability.

In 1959 the barriers were finally broken when arguably the theatres leading light, Sir Laurence Olivier, made what was described as an "electrifying television debut" in Ibsen's John Gabriel Borkman. And with the removal of that barrier the floodgates opened. Sir John Gielgud made his debut alongside Gladys Cooper, Margaret Leighton, Roger Livesey and Megs Jenkins in A Day by the Sea. It was one of the most impressive cast lists ever assembled for a single play, let alone a television broadcast.

Sir Michael Redgrave appeared in the moving role of a schoolmaster in N.C. Hunter's A Touch of the Sun, a part that had previously won him "Actor of the Year" in 1958. And this encouraged others to recreate their stage roles for television, as did Robert Helpmann, when he transferred his great success in the West End production of Noel Coward's comedy Nude With Violin to the small screen. ATV signed Peter Draper to write exclusively for them and his first play, The Paraguayan Harp starred Maurice Denham. His next play, Sunday Out of Season, the story about a romance in a small seaside town, starred Maggie Smith, who also gave a memorable performance in A Phoenix Too Frequent alongside George Cole. As well as the now well-known names to appear in the cast lists a number of celebrated authors figured amongst the credits too. Thornton Wilder's famous story The Bridge of San Luis Rey was presented as the first play of 1959 and starred Diane Cilento. Poking fun at convention and society was both Ian Hay and L. du Garde Peach who collaborated in The White Sheep of the Family, a lightweight comedy about a family who owe their comfortable living to their combined talents as pickpockets, burglars and forgers.

Jean Anouilh's The Traveller Without Luggage took more than 25 years to reach the British stage, but considerably less time to make it onto television, adapted and directed by Casper Wrede the play featured Keith Michell and Michael Gough. By the end of 1959 ATV had produced a vintage year for television drama and along with the rest of its output was going from strength to strength. The following year it was announced that the channel would be ousting all cinema feature films from the weekend TV schedule, in what was described at that time as a "revolutionary step". Val Parnell explained at the time the reason for that decision:

"Our combined programme resources now make it possible for us to bring more live productions and several new TV film series from Britain, Australia and American studios." One of the first results of this new policy was the screening of Theatre 70, a series of 70-minute plays, all concentrating on a suspense theme and spawned by a series of plays called Suspense that had been well received earlier in the year. At that time one of Parnell's partners, ITC board member Lew Grade would almost certainly have one eye on possible US sales, and the first play featured Robert Horton, better known for his role as Flint McCullough in Wagon Train.

'No Gun, No Guilt' starred Ann Lynn, David Knight, Margaret Vines and Leo McKern

As drama series' gathered in reputation so they attracted some of British theatre's best-known faces and names such as Flora Robson, Gracie Fields, Joan Greenwood, Charles Gray, and Donald Pleasance. Lesser-known names, debuting in British television drama, would go on to enjoy long and distinguished careers and these included Alan Bates, Tom Courtney and Diana Rigg.

1958 and 1959 were clearly pivotal years for British television, and the following decade would be fondly remembered as the true golden age of quality television drama. More so than at any other time in the medium's history, the 1960s would establish itself as the decade during which the one-off drama truly came of age on British television screens.

In 1962, Sydney Newman suddenly left ABC to take up the role of Head of Drama for the BBC. Leonard White believes that decision may have been influenced by changes at ABC that Newman was not happy with. Brian Tesler, who had been brought in to develop Light Entertainment', had become Programme Controller. Whereas Howard Thomas had been happy with ABC being the major provider of drama for the ITV Network, leaving Lew Grade's ATV as the main provider of LE, the emphasis was now about to shift. As a result, and while Newman was on holiday, ABC lost the weekly Armchair Theatre slot to a fortnightly only slot. When Newman quit (he was so incensed that he even took a drop in salary at the BBC) he was replaced at ABC by Leonard White who went on to produce 165 teleplays up until 1969. White, the original producer of The Avengers who had cast Honor Blackman in the role of Cathy Gale, was also trained at CBC in Toronto.

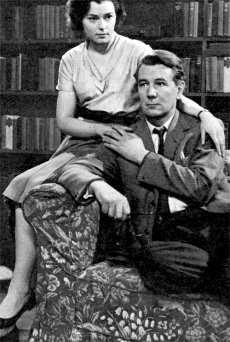

Harry H. Corbett and Miranda Connell in The Hot House, broadcast on 13 December 1964. The play featured the television debut of Diana Rigg.

At the BBC Sydney Newman set about revamping the Drama Department into three separate units: Plays, Series and Serials. One of his first priorities was to revive the BBC's reputation for serious drama which was at its lowest level in eight years. In September 1963 Newman launched First Night, a series of new plays written especially for television. Alun Owen's The Strain and Simon Raven's The Scapegoat were among the notable dramas produced between 1963 and 1964. But it wasn't until Newman launched The Wednesday Play that the BBC's fortunes began to turn around. With dramas from Dennis Potter, John Hopkins, David Mercer, Jeremy Sandford, David Rudkin, Jim Allen, Tony Parker, Nell Dunn, and Colin Welland, The Wednesday Play was to have an even greater impact than Armchair Theatre.

British television, in parallel with the emergence and rapid growth of the serious drama form on American television screens of the latter part of the 1950s and for much of the 1960s, was closely associated with quality productions, and laid the roots for dramatic presentations that continually broke new ground, as with plays like Stand Up, Nigel Barton and Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton, Up the Junction and the oft-mentioned Cathy Come Home. Through these years and into the following decades it also brought us the work of many gifted writers and left us with many memorable performances; Patricia Hayes in Edna, The Inebriate Woman, Alison Steadman in Abigail's Party, Nigel Hawthorn in the Jack Rosenthal play The Knowledge, John Hurt in The Naked Civil Servant, Mike Leigh's comedy Nuts in May and Alan Bennet's An Englishman Abroad, have all placed themselves indelibly into the annals of television history, as proved when each of them was named in the British Film Institutes top 100 programmes of all time, which was compiled at the turn of the millennium.

Through strands such as Armchair Theatre, The Wednesday Play and Play for Today, the single drama consolidated its position as not only the worthy equal of its traditional theatrical counterpart, but also established itself beyond question as an immensely powerful and relevant mirror to the swiftly changing social evolution of the nation at large.

Next Article: Missing, Believed Wiped: The Lost Treasures of British Television

Article

Laurence Marcus (February 2007) Reference Sources: The Armchair Theatre (published 1959), The Guinness Book of TV Facts and Feats, The Television Barons by Jack Tinker, ITV: The People's Channel by Simon Cherry, The Television Annual for 1959.

History and Notes:

When Independent Television began in 1955 American comedy series like 'I Love Lucy' topped the TV ratings poll; then came the quizzes with extravagant prizes; then the boom in Westerns. Lavish variety shows, better produced than ever before, topped the ratings in the early years, but even the most intrepid acrobats and the most gravity-defying jugglers wore out their welcome, so that there was only room at the top for big-scale, big-name shows like 'Sunday Night at the London Palladium'.

Through all this, plays remained high in public demand. In the ten most popular programmes in any week, you were certain to find a play or two. Britain liked its drama and was prepared to sit down almost every night of the week to 'a good play'.

For this, much credit must go to the BBC. The Corporation had always given drama an important place in its schedules, from the days of Val Gielgud's radio plays to Michael Barry's regime in television (this will be covered in another article). Even when television budgets were skimpy the BBC allocated generously to drama, encouraging writers, training directors and technicians. All this pioneering was rewarded by the standard of television drama and the response of the audience.

Independent Television first took the bulk of that audience away from the BBC by putting on more acceptable light entertainment, but the real battle between the two channels was in the field of drama. The BBC's powerful, large and firmly-established Drama Department was presenting three plays of a generally high standard week after week. But when the Drama Departments in the Independent Television Companies came into life they flourished and prospered until they overtook and outpaced the BBC's output. By the late 1950s, almost without exception, the audiences with a choice between a play on BBC or ITA were choosing the ITA play on a ratio of three to one.

ITA plays were regarded as lighter and livelier because of the BBC's policy of presenting the whole range of drama, from farce to classics, in their entirety. The viewer preferred the ITA's one-hour play as part of a varied evenings viewing whereas the BBC productions ran into two and three hours, demanding attention and concentration for most of the evening. Not that the ITA play departments had left the serious field to the BBC, for some of the most vigorous and exciting revivals of Ibsen and Strindberg came from the independent channels, along with some of the most serious and controversial plays of the contemporary theatre.

- Adapted from the 1959 ABC Television publication 'The Armchair Theatre', a comprehensive book on the television play intended for "all those wishing to make a contribution to this new art", the above article is made up of contributions from Howard Thomas, Managing Director of ABC Television Limited, the company that presented 'Armchair Theatre'. The establishment of 'AT' was the result of Thomas's conviction that the play was the principal common denominator in family television entertainment. Producer-Director Dennis Vance also pioneered the series.

Some 1950s Plays:

The White Sheep of the Family starred Diane Clare, Gareth Davies, Marian Spencer and Newton Black

A Day by the Sea with John Gielgud, Margaret Leighton and Gladys Cooper

A Touch of the Sun with Michael Redgrave and Jayne Muir

John Gabriel Borkman with Laurence Olivier and Anne Castaldini

A Phoenix Too Frequent with George Cole and Maggie Smith