The History of ITV - Part 9

Val Parnell

Parnell threw caution to the wind and started to pay fabulous sums of money to bring to the Palladium the cream of the world's talent.

By the late 1940s Val Parnell had established himself as one of Britain's foremost theatre managers and impresarios. Through his association with Lew Grade he was also instrumental in the popularisation of television following the launch of ITV in 1955. The many variety shows he produced played a crucial role in establishing the new commercial channel. He may have been seen by many as an empire builder, but by the end of 1962, Parnell's empire was crumbling.

Born in London on St. Valentine's Day - 14th February, 1892, Valentine Charles Parnell was the son of veteran entertainer and ventriloquist Fred Russell. He began his theatrical career in 1907 as an office boy for the Moss Empires theatre circuit. By 1945 he had risen through the ranks to become the right-hand man to George Black, Managing Director of Moss. Black also controlled the London Palladium. Parnell was the Booking Manager of the company, the man responsible for engaging all the artistes playing at the company's theatres. In 1943, Parnell persuaded Black to bring to the Palladium a relatively unknown comedian who had been playing the provincial circuits for almost thirty years - his name was Sid Fields. In Strike a New Note, Fields, who came from Birmingham, appeared as Slasher Green, a Cockney 'wide-boy' or 'spiv.' He was an instant hit and became a West End star overnight. Parnell took no credit for the discovery. He simply told reporters "anyone can pick a star but not everyone has the courage to start him in the West End. But George did."

Following Black's sudden death on 4th March 1945 (at the age of just 54 years), Parnell became Managing Director of Moss. It was then that he took complete charge of the Palladium itself. When most of the theatres up and down the country were closing down due to poor attendances, Parnell threw caution to the wind and started to pay fabulous sums of money to bring to the Palladium the cream of the world's talent. When he was criticised for favouring American artists, he responded with "My job is to fill the theatre. If I feel British artists can do it, they will get the chance."

The first of these American acts to arrive was Mickey Rooney, but the Hollywood star received only a mixed reception. Then US superstar Danny Kaye arrived and proved to be a resounding success. For an hour he held the stage, talking, singing, dancing, chatting with the orchestra. He was a sensation. Kaye received rave reviews from the critics and for his third performance a thousand people queued outside the theatre's box office from Argyll Street to Oxford Street, lining up for just 350 "standing room only" tickets. Another popular visitor to the Palladium was Jack Benny, who had been brought over to England for the first time by Lew Grade. Benny was nervous at first about appearing on stage in another country but received such a warm welcome that he returned on numerous occasions. Interviewed towards the end of the decade, Benny said, "I think Parnell knows more about vaudeville than any man in the business."

Parnell's right-hand was his secretary Miss Woods and his booking controller was Cissie Williams. According to Chris Woodward's history of the London Palladium (The London Palladium: The Story of the Theatre and its Stars) "nobody, but nobody, crossed her." Parnell had very strict rules about the Palladium and ensured everyone abided by them. "The very heavy fireproof pass door between stage and the auditorium had a one-way traffic policy" wrote Woodward. "Parnell could go up the few steps to the stage, but if any artist was caught coming the other way he would never work the theatre again. Such was his eye for perfection, often during a show Parnell would enter through the pass door to complain about the smallest detail."

The old order was changing...

By the mid-1950s Commercial Television was coming in, and to many people it appeared to pose a threat to theatres across the country. The old order was changing, and Val Parnell was one of the first to realise what this meant. When Lew Grade invited Parnell to help form the board of one of British televisions first commercial channels there is no doubt that Grade had his sights firmly set on the golden egg of the variety theatre with all its previously untapped (for television) talents. Up to that point theatre owners and booking agents up and down the country had resisted the lure of television fearful that it would spell the end of live theatre. Grade knew full well that the London Palladium could easily become the foundation on which Commercial Televisions success was built.

Val Parnell's Sunday Night at the London Palladium aired for the first time on 25 September 1955. I would argue at this point that while growing television audiences may have taken ticket sales away from the so-called legitimate theatre, it did nothing to damage variety theatre numbers throughout the 1950s and 1960s. On the contrary, a successful appearance on a TV variety show such as Sunday Night at the Palladium, giving stars extra exposure and continually introducing them to new audiences, could do wonders for box-office takings and many a summer season was sold out on the strength of an appearance on a TV variety show. Even up to the 1980s Morecambe and Wise could guarantee sell-out audiences for live shows and in the early 2000's variety talent shows such as How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria? and I'd Do Anything ensured sell-out runs in the West End. In truth, it wasn't variety on television that damaged theatre audience sales - it was the lack of variety (especially throughout the 90s) that caused it.

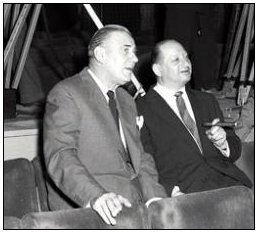

Grade and Parnell were two complete different sides of the same coin. According to Jack Tinker's book The Television Barons, Parnell's lifestyle couldn't have been more different from the workaholic Grade. "His custom-built suits, his taste in expensive wines and women to match, his liking for leisure weekends on prime golf courses in luxury love-nests, were not in Lew's line at all. Moreover, unlike Lew, who in his day could boast that though he had countless rivals he had no enemies, Parnell's power and modus vivendi made him not only feared but heartily disliked in many quarters." Rita Grade Freeman, in her book, My Fabulous Brothers wrote of Parnell "he was a man who just had to have the adulation of other women. One woman could never satisfy him." Parnell had married a former dancer, Helen Howell, but that didn't stop him from having affairs. Eventually, Helen divorced him for restitution of her conjugal rights in a blaze of unwelcome publicity that contributed to his 'resignation' from ATV. Jack Tinker explained: "There was, of course, no secrecy about his genuinely loving liaison with Miss (Aileen) Cochrane in the circles in which they moved. But the permissive society had not then reached semi-detached suburbia or the family audiences Parnell liked to cater for in his theatres and at ATV. In those more prim days, as managing director and virtual programme controller of such an influence on public morality as Associated TeleVision, he was almost as vulnerable to any irregularities in his matrimonial arrangements as the Archbishop of Canterbury."

Moss Empires was open to a skillfull takeover - the prize was some of the finest theatres in the country headed by the London Palladium...

Lew Grade, at that time would refuse to be drawn on Parnell's private life, only pointing out his value as a colleague and describing him as "a genius." But in November 1960 things began to change. Parnell had joined forces with Lew's brother, Bernard Delfont and millionaire businessmen Charles Clore and Jack Cotton for a takeover of Moss Empires. In his autobiography, East End, West End - Bernard Delfont described what happened. "(Moss Empires) was open to a skillful takeover. The prize was some of the finest theatres in the country headed by the London Palladium and the Victoria Palace. Moss also owned the biggest stake in Associated TeleVision; two-thirds of the voting shares. A lunch was arranged for Charles to put across to Prince Littler the arguments for a takeover. (But) whenever the conversation moved from generalisations to specifics, he countered repetitively: "I'll have to think about that."" Littler didn't spend too much time thinking. Gathering all his financial resources, he immediately moved to buy up all the preference shares in Moss Empires that were not already in his hands. It was a move that Clore had overlooked. Even so, Clore, Delfont, Cotton and Parnell were still confident of mounting an acceptable and successful bid, estimated to be in the region of £5 million. Delfont explains what happened next. "I had reckoned without Jack Cotton. Having so far stayed in the background he now felt bound to make his contribution by sounding off to reporters on what he would do with the Moss theatres once we had moved in. In his view, they would make wonderful office blocks. I could only close my eyes to shut out the horror. The Palladium, an office block. Unthinkable."

Prince Littler, Parnell's partner at Moss and also the Chairman of ATV was outraged. His reaction was swift. With Parnell out of the country Littler called a board meeting at which he forced the board to vote over to the company Parnell's own 1,300 preference shares. Upon his return, Parnell threatened to sue Littler on the grounds that he was, as a director of the company, entitled to be present at the board meeting. Littler responded that he had been unaware of Parnell's absence. When pressed on this he coolly responded "He was often absent." The implication couldn't have been clearer. By the end of December, Parnell sold his shares and resigned from the board. He was out of Moss Empires and out of the London Palladium.

Parnell decided to stand firm on his position at ATV. "It is impossible for Littler to force me out of my job as Managing Director of ATV." He told reporters - "I'm fireproof." Parnell did remain at ATV for another two years, until his private life became the subject of press attention. One night, in September 1962, Parnell was sitting down to dinner in his home with Aileen Cochrane and one of his employees, Roy Mosely, who was there to discuss business when the phone rang. Mosely took up the story: "He (Parnell) left the room and took the call. When he came back after a very short while he was...well, I can only describe it as ashen. He sat down and just said to Aileen: "Lew's fired me." It wasn't until I got home that I realised that Parnell was Lew's boss on the board at ATV." Parnell announced his intention to go down fighting. But a week later, on 26 September 1962, he resigned from the board of ATV. The following year his wife's divorce petition was heard and his affairs became public. It is most likely that Grade had estimated the adverse publicity well in advance and finally decided to distance himself from Parnell. Grade was Parnell's last ally on the board of ATV and once he had withdrawn that support - Parnell's position became untenable.

In public Lew Grade remained loyal to the Parnell legacy. The title of the Sunday night Palladium show continued to carry Parnell's name until September 1965 when it was renamed The New London Palladium Show, becoming simply The London Palladium Show from January 1966. In his autobiography, Still Dancing, Grade wrote "Val had been going through some matrimonial problems and decided he could no longer give ATV the necessary time. In fact, he retired completely, although he remained on the Board for a little while. This was quite a wrench for me. Our association went back so many years, and we had gone through so many exciting experiences together, that I knew I'd miss him terribly."

Parnell finally resigned from the board of ATV in 1966 to live in retirement in France. He died on 22 September 1972.

The History of ITV Part 10: Sidney Bernstein

Biography: Laurence Marcus, 2010. Sources: The London Palladium: The Story of the Theatre and its Stars by Chris Woodward. The Television Barons by Jack Tinker. The Television Show Book (various). My Fabulous Brothers by Rita Grade Freeman. Still Dancing by Lew Grade. East End, West End by Bernard Delfont

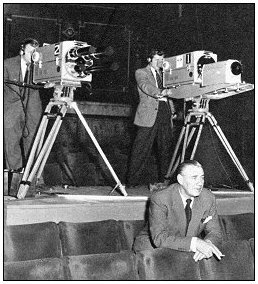

Debuting on the first weekend of commercial television in the UK, from the very start Sunday Night at the London Palladium established itself as the highlight television show of the week for Britain's viewing millions - and immediately climbed to the top of the TV ratings.

The show was the topic of conversation for millions in factories, offices and shop floors on Monday mornings and it even prompted one Church of England vicar-the Rev. D.P. Davies, of Holy Trinity Church, West End, Woking, Surrey-to start his Sunday evening service half an hour earlier, so that his congregation could get home in time to see the show.

The British viewing public had never seen anything as spectacular as this on their TV sets before as the world's most celebrated stars and the best of home-grown talent was bought into their living rooms in an extravaganza of music, dance and comedy. Sunday Night at the London Palladium was very probably the one show, above all others, that helped establish Commercial Television.