History of the BBC - Part 10

Designed for Women

If 1946 was the curtain raiser on post-war television then 1947 was the year that the BBC began exploring the different types of programming it could offer viewers for the first time. These included a number of outside broadcasts such as the Trooping of the Colours, the Service at the Cenotaph as well as sports events such as the FA Cup Final at Wembley and the University Boat Race. Among regular studio programmes was one old favourite and a new one. Picture Page, edited and introduced by Joan Gilbert, continued its weekly parade of personality interviews, and Kaleidoscope established itself as the viewers' own magazine programme. The television documentary began to evolve a technique of its own and Philip Harben, as television cook showed cookery in close-up, while Fred Streeter tended the Television Garden. The one thing that was missing was a women's programme made by women. But thanks to Mary Adams, Jacqueline Kennish and Jeanne Heal it was not too long before this type of programme became a staple of early afternoon broadcasting.

Jeanne Heal was born on 25th May 1917, and at one time it seemed that she was destined for a career in architecture. Having an architect father, this was the idea. Her own inclinations, however, lay in journalism, and she started out in that sphere in the provinces. When London finally beckoned it was not newspaper work that bought Jeanne to the capital. Instead she took up an offer with a London advertising agency where she was employed to write advertising 'copy'. When the Second World War broke out she joined the Land Army.

Jeanne was stationed in Gloucestershire, and she occupied her weekend 'leaves' by hitchhiking to London, usually through Saturday night. At first the effort proved to be full of interest for her seeing the different sights and meeting interesting people, but after several weeks the trudge proved to be tiresome. Still, she reasoned that if the journey held interest for her initially then perhaps other people would like to hear about it. So she wrote to the BBC suggesting a radio talk show about her weekly journey and the BBC took her up on it. Perhaps a bit cheekily, Jeanne told the BBC that if they really liked the idea they would have to have someone meet her on a Sunday morning when she arrived in London.

To her surprise, the following Sunday, she was greeted on her arrival by a BBC official and was immediately given a date for the talk. It was to be a 'one-off' but the first broadcast was heard by a Ministry of Labour official who contacted the BBC suggesting that this girl could do a great morale boosting job by talking on the radio about life in all the women's wartime services. With her job officially sanctioned by the Government Jeanne served through all the different women's services spending several months in each, and broadcasting her impressions of how she found them. By the end of the war hers was a familiar voice on radio and her services were retained by the BBC as a broadcaster on Woman's Hour, and in the BBC's overseas services. At the same time she was writing a regular column for a national newspaper as a specialist in woman's interests and fashion.

Through her connection with the fashion world she was approached by BBC television to see if she would consider commentating on a womans millinery show at Alexandra Palace. She turned up expecting to discuss plans for the show only to find that the programme was due to go to air straight away and was unceremoniously thrust in front of the TV camera. Still, the BBC must have been suitably impressed with the way she acquitted herself because soon afterwards she was approached by the head of women's programmes, Mary Adams (who had been at the BBC since 1930), to come up with an idea for a regular women's television feature.

Designed for Women was Alexandra Palace's first women's programme. The earliest programmes were broadcast in 1949 and marked the beginning of a collaboration with a former journalist, Jacqueline Kennish who had been hired as a producer in 1948. One of the earliest programmes had Jeanne talking to Elspeth Huxley about womens life and education in East Africa, a piece on the life of a farmer, and the everyday problems of small children. Jacqueline Kennish had been a reporter for 'Time' magazine in London throughout the war and was more in tune than most to who and what was most interesting in America. As a result on one of the Designed for Women programmes she brought to life 'The Last Flower', a satirical story by American cartoonist James Thurber, about a man, a woman and a dog, the only survivors of a world war. This was done as a kind of animation piece, showing all 60 drawings accompanied by specially chosen music. Designed for Women was broadcast in the afternoon and was compeered by Jeanne Heal who, in 1950, also 'conducted' a new programme for women called Women of Today.

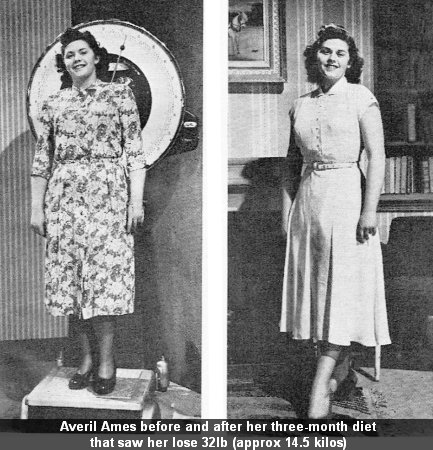

It would appear that Designed for Women caused some controversy in 1951 after offering to supply women with diet sheets. The BBC incurred the wrath of the British Medical Association and a certain Lord Horder insisted on appearing on the show to put the medical view across. The show obviously proved successful though as showgirl, Averil Ames, was used to illustrate how well the diet worked by being the before and after model. She lost 32lb in three-months.

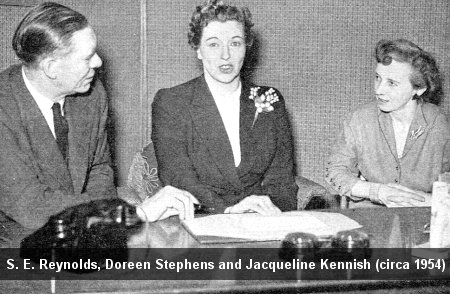

Probably as a result, the BBC began casting about for replacements, according to records from the Caversham archives, S.E. Reynolds, a male producer was charged with finding a team to create some new programmes to replace Designed for Women. Jacqueline Kennish was one of his picks to edit the programme while he produced it but Jeanne's name was not even mentioned at first. He proposed using Joan Gilbert from Picture Page to introduce one of the programmes. But within a few days of that memo, Jacqueline wrote a memo to both Reynolds and Jeanne with her ideas on the new programme to air that October. This programme was Leisure and Pleasure. Amongst her ideas for the programmes, she suggested a segment on the week in parliament, an interesting personality-a celebrity, a policewoman, a student, or someone with a particularly interesting job-a 'how to' piece that might include tips on how to give a speech, rather than the usual home-making items, book and film reviews and, at Jeanne's suggestion, that might include something on those who work behind the scenes, as well as something on contemporary design from the collection of the Council of Industrial Design. If there was to be a fashion piece she suggested using students from the Royal College of Art or St. Martin's to give the piece a slightly different twist.

The collaboration with Jeanne as compere continued with great success for several years after Jacqueline pointed out to S.E Reynolds, that for him to change things on the floor after she had set up the programme made her work "rather pointless." Later programmes of Leisure and Pleasure included segments on art, designer Mme. Schiaparelli's use and naming of the colour, shocking pink, Ann Davidson, the first woman to sail the Atlantic alone, Col. Harry Llewellyn and his horse, Foxhunter, who won Britain's first Olympic gold medal after the war. Foxhunter was the only 'guest' who managed to briefly disturb Jeanne's usual poise by gently sniffing at a rather large corsage strategically placed on her décolletage.

These 'illustrated talks' programmes as the BBC referred to them, proved a great early success for the BBC and their own audience research discovered that they clocked up 61 marks out of a possible 100 for the best-liked programmes. The TV talk shows were already beginning to outscore the radio versions in popularity with 'unillustrated talks' only scoring around the 34 mark. The following year Jeanne Heal moved into more serious documentary programmes as the BBC expanded with two TV departments providing informational programmes; the Talks Feature Department and the Documentary Department. While Christopher Mayhew appeared to concentrate on the political issues of the day Jeanne Heal went for the more human-interest stories in a series called Case Book and in particular a series of shows she did on handicapped people, Struggle Against Adversity, proved to be very emotive.

Both series were pioneering in the subject matters they bought into the comfort of the BBC viewing audiences home, proving that even in these early days television was not there simply to entertain but also to inform. The programmes were deliberately designed to probe circumstances of people who had suffered misfortune such as paralysis and blindness but also didn't shy away from controversy and were obviously seen as daring in the subjects they tackled such as alcoholism and illegitimacy. Jeanne Heal was much admired at the time for not parading these facts mawkishly but in a frank and honest manner as the most natural and uninhibited truths.

In 1954 Mary Adams departed to make way for new editor of women's TV programmes, Doreen Stephens. The new editor was tasked with expanding the popular format and introduced two new programmes with the catchy titles Make The Best Of Yourself and New Interests On Your Doorstep. Whether these shows actually caught on is not known as there appears to be very little in the way of documentation of either of them or one that Miss Stephens had in the pipeline tentatively titled Family Affairs. What is known is that Leisure and Pleasure, still introduced by Jeanne Heal and produced by Jacqueline Kennish, continued to pull in early afternoon viewers.

By 1955/56 Mary Adams had been appointed Assistant Controller of the BBC and Doreen Stephens was heading a show called Women's Fare. Jeanne Heal had now moved away from women's programming completely and had joined forces with Aidan Cawley and Christopher Mayhew to present medical features in Panorama. At about the same time, May 1955, Jacqueline too also contributed to Panorama, but was listed only as a researcher while Grace Wyndham-Goldie, not known for her support of other women, according to her biographer, John Grist, was already presenting some election coverage. Although Panorama would later concentrate much more on current affairs in its early days it tended to be a mixture of the arts, human-interest stories and scientific or medical topics. This was the vision for the programme of new Head of Talks Department, Leonard Miall, who wrote in the 1955 'Television Annual' that he saw Panorama as a piece of enterprising television journalism that needed to leave current politics and national affairs to programmes such as Viewfinder. Meanwhile Panorama as the title suggested took a much wider look at life and never shied away from controversy. A 1954 edition showed viewers how a dentist could remove a tooth from a patient while she was under hypnosis. Apparently, the patient, nineteen-year old Sylvia Langley, proved to viewers that the operation could be done quite painlessly.

But towards the end of 1955 things were changing rapidly at the BBC. Independent Television was luring away many of the Corporation's best talents, not only from in front of the cameras but behind them, too. Jacqueline Kennish, one of the creative forces behind many of the early afternoon shows for women joined the exodus to ITV to do a programme called The Lively Arts. Jeanne Heal was seen less and less on television and the era where afternoon television was 'designed for women', was coming to an end.

Part 11: Norman Collins - An Independent Man

Article

Katherine Wright and Laurence Marcus. June 2007. Other references: The Television Annual (various editions 1953 to 1956).