History of the BBC - Part 11

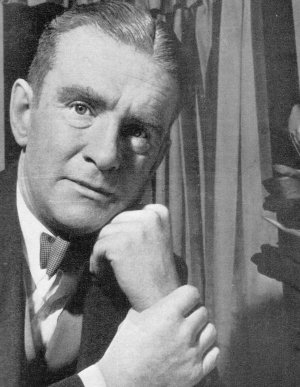

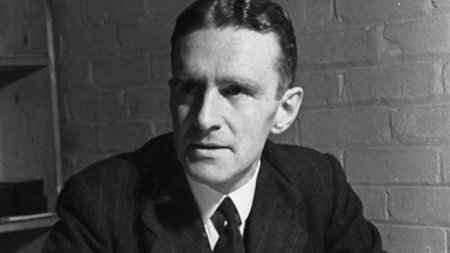

Norman Collins - An Independent Man

Born on 3rd October, 1907, in New Beaconsfield, Norman Richard Collins came from a French-Huguenot background on his father's side and Welsh farming stock on his mother's. The family home was dedicated to the arts and young Norman showed early promise when at the age of eight he wrote and illustrated a school magazine which he then loaned to friends at a halfpenny a time. On leaving William Ellis School, Hampstead, at eighteen he got a job at the Oxford University Press and within two years he was at the 'News Chronicle' as assistant literary editor, where he wrote a column called 'London from a Bus Top.' At 21 he wrote a survey of the English novel. At 23 he joined Victor Gallancz's publishing firm where, between heavy desk work and trips to America, he wrote a novel under an assumed name, sent it to Gallancz's and had the fun of seeing them accept it. He stayed at Gallancz's until 1941 becoming Deputy Chairman.

Touring provincial bookseller's, he wrote a novel about commercial travellers and after reading a book about the fauna of the East Indies, he wrote a novel about Penang. Not content with stopping there, he began reading books about South America and wrote a novel about that land and for it, to his great surprise, was elected Honorary Vice-President of the Bolivian Geographical Society. His 1930's novel 'London Belongs to Me' was made into a feature film in the late 1940's.

But before that, in 1941, Collins joined the BBC as an assistant in the Overseas Talks Department and began a meteoric rise through the ranks. His first promotion, by April of the same year, was to that of Empire Talks Manager followed by General Overseas Services Manager then General Overseas Programme Services Director. During the war he rocketed around the battle areas, finding out what the armed forces wanted to hear on the radio. And when Maurice Gorham, who had started the Light Programme, left it to re-open the Television Service, it was Collins whom Sir William Haley, Director General of the BBC, called in to take controllership. At the Light Programme Collins created two of the most iconic programmes in the history of British radio broadcasting. The first of these was the adventure series 'Dick Barton: Special Agent', which ran for over 700 episodes between 1946 and 1951 and drew 15 million listeners at its peak, and the second programme Collins initiated was 'Woman's Hour', which still runs to this day.

When Maurice Gorham resigned from Alexandra Palace in 1947, Haley again called on Collins and sent him to the chair of Controller of Television. Many people within the industry had Collins earmarked as a future successor to Haley as Director General. His appointment as Controller coincided with the move towards television becoming a mass medium with licence numbers breaking into six figures for the first time. Even so, when he entered television many people outside the industry joked that the medium "had a great future, but no present."

Collins had an immediate impact at Alexandra Palace even though he candidly admitted he knew little or nothing about television. He promptly set about the task of learning and in a very short time had a firm grip on the job. Before long Collins was not only commanding attention within AP, but without. He was badgering away at the Government for more co-operation-and getting it. Perhaps the high point of Collins' time in control of the channel was the broadcasting live on television of the 1948 Olympic Games at Wembley. The first 'Games' to be televised into people's homes (the 1936 Olympic Games were televised locally in Berlin to specially set up 'television booths' in selected viewing halls). The BBC had offered 1,000 guineas for exclusive broadcasting rights. This was the first Olympic Games to establish the principle of the broadcast rights fee. However, concerned about financial hardship to the BBC, the OCOG (Organising Committee for the Olympic Games) did not take the payment. In anticipation of the event it was claimed that the number of receivers in the London area had increased from 14,550 in 1946 to 66,000 by 1948. Sir Arthur Elvin, the managing director of Wembley Stadium, lent the BBC the old Palace of Arts, constructed for the British Empire Exhibition of 1924, to serve as a broadcasting centre with 8 radio studios and 32 channels. 15 commentary boxes were installed with 16 open positions in the stadium and 16 commentary points at the Empire Pool. The huge task of laying coaxial cable between Wembley and Broadcasting House was put into operation requiring the mobilisation of staff and equipment not just from London but also the regions.

Under blazing sunshine and the watchful eye of 82,000 stadium spectators and the BBC television cameras, the 14th Olympiad opened at 2.45pm on Thursday 29th July, 1948. Peak events were allowed to break into scheduled afternoon programming. The title of the daily programme was 'Olympic Sports-Reel 4'. A camera was used overlooking Olympic Way to catch pictures of the crowds as well as the contestants. Two mobile units were controlled from a radio centre in the Palace of Arts: one unit in Wembley Stadium itself, the other at the Pool. Each commanded three cameras, with producers watching events on monitors and drawing on the stories of a dozen commentators. BBC television broke all records during the Olympic Games in arguably the greatest fortnight in its history. By the time the Games finished on August 14th, the Corporation had broadcast 68 hours and 29 minutes, or an average of almost five hours of television a day. More than 500,000 viewers watched the televised events.

In spite of this great success Collins was faced with a lack of studio space, lack of modern equipment, lack of personnel and a lack of money. The dilemma facing the BBC at the time was it was still committed to maintain its mammoth organisation of sound broadcasting and television was very much secondary to its plans. One TV critic wrote about Collins at the time "For a man who has never stayed in one place long, his future probably depends on whether he, almost alone, can do what is necessary to give television development a speed geared to that of his own high-velocity career." They proved to be prophetic words. Collins suffered many of the frustrations felt by his predecessor, Maurice Gorham, about the lack of support from his own bosses within the BBC. In 1949 he travelled to the USA to see how television was developing in a country that was prepared to invest in its future development with big dollars. On his return he wrote: "...once television is truly national it will become the most important medium that exists. Everything that it does or does not do will be important. The very fact that it is in the home is vital. Its only rival will be the wireless, and the rivalry will not be strong." And in a statement that probably sent shockwaves throughout the BBC he concluded: "...the first casualty of television, possibly the only casualty, is not the local cinema or the country theatre, it is sound radio."

There is every chance that as soon as his comments were published in the April 1949 edition of "BBC Quarterly", Collins' days at the BBC were numbered. In the end he was pushed so far - he jumped. In his book 'The Television Barons', Jack Tinker wrote: "Collins himself always claimed that he was forced into the direction he took by the BBC itself. Certainly his views on the future of broadcasting diametrically conflicted with those of Sir William Haley, and could not possibly have co-existed within the same organization. Furthermore the reasons for his resignation as head of BBC TV only serve to convince many fair-minded people, both inside and outside the cradle of democracy, that the Corporation's control of our broadcasting system had become a most dangerous threat to the fundamental rights of free expression."

"What started it all was a mildly satirical trifle of a play - how trifling may be judged from the title - called 'Party Manners' and written by Val Gielgud. It poked fun at politicians and implied that socialists also had itchy palms willing to be scratched. For this heresy, Lord Simon, the Chairman of the BBC, decided to scrap transmission of the live repeat of the play (there were as yet no tele-recordings of the traditional Sunday play)." The BBC had, it seems, put into place the wheels of motion that would strip Collins of his power. Just to compound matters, within the next seven days, the BBC passed up Collins for the job of Controller of Programmes, handing the position to George Barnes, Controller of the BBC Radio station, the Third Programme, a man without any experience of television. Forced into an impossible position, Norman Collins resigned.

The following weekend, the 'Sunday Express' ran a cautionary article, written by Collins, about the BBC's monopoly: "It is unhealthy for the corporation because it means that some members of the staff remain there, patiently and miserably working out their time, for the simple reason that they know only too well that their single, specialized talent is totally valueless and un-saleable outside. It is equally unhealthy for the person who resigns. He is apt to fall into the dangerous mental state of believing that he is the only one in step. He may have been. Or he may not. The one thing that is certain is that he will never know, because there is no wholesome corrective alternative employment that might disabuse him." Within five years there would be. And Norman Collins would play one last major role in the changing face of British television.

Article

Laurence Marcus, May 2nd 2008. Sources of reference: The Television Annual 1950/51 - Here's Television by Kenneth Baily 1950 - The Guinness Book of TV Facts and Feats by Kenneth Passingham - The Television Barons by Jack Tinker

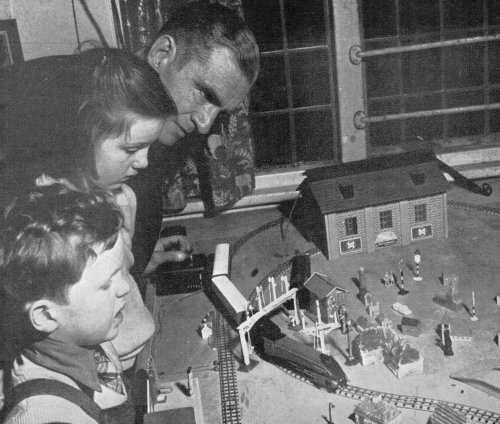

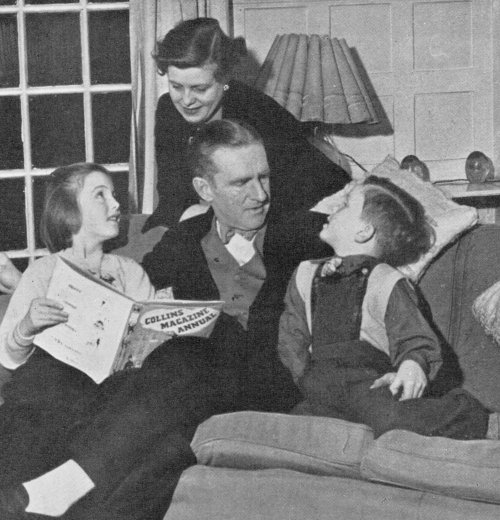

In 1953, Collins was pictured at home in Golders Green with his family by the photographer of TV News magazine. At 46-years-of-age, he is seen with his wife sarah and children Anthia, Andillia and Roderick, with (in the last picture) their dog, Maundy.