History of the BBC - Part 3

Here's Looking At You

There was one item on the list of staffing jobs which Gerald Cock felt to be of great importance. Television would need something new in announcers. Given the voice, and usual impeccable accent, the radio announcer was not that hard to come by. But now radio had eyes, and its announcers were going to be seen, day in day out. It was no use looking for a mere Adonis or a Venus; it is one of life's little jokes that perfection of face and figure is rarely accompanied by a thoroughly likeable personality, let alone the brains and wit to deal with emergencies - and the odd folk, who, in television, would no doubt cause the emergencies.

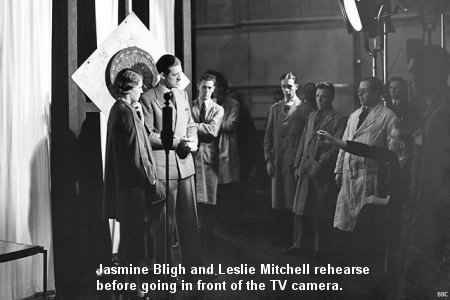

Cock believed in glamour, but knew that television comes intimately into the home, and that warmth of personality, without either affectation or artificiality, would be required of its announcers. He advertised for one man announcer, and two women, and himself concentrated on the trickier job of selecting the ladies. Seven hundred young women applied! His final choice led to some criticism, because both young women were well-born adornments of what used to be called "London Society," and not the sort of girls to be in crying need of work. Though I never dare ask him, I think Cock would probably have said that for savoir faire, dignity of bearing and charm you could not beat the socialite strata of hard Mayfair training. Probably he would have been right. Certainly Elizabeth Cowell and Jasmine Bligh had "it all"; as well as a natural friendliness which was to glow from the home screens and make them the friends of every viewing family. There was a lot of injudicious publicity about the glamorous wardrobes being collected for these two girls, but nobody will ever be able to deny that they gave television a distinctly visual flying start.

Selecting the first man television announcer was altogether a more staid and plain proceeding, true to BBC practice. Over 600 young men who considered their faces worth broadcasting into the homes of the people, applied for the job. That kind of male handsomeness which, rightly or wrongly, is often associated with " gay goings on" straight away eliminated a good half of them -some, I have no doubt, quite unfairly. But in television appearances do count!

The winning applicant was practically unknown, though he was already on the BBC payroll. Haunting St. George's Hall, headquarters of the BBC Variety Department, as I did in those days, I had noticed a fine, upstanding youngster bearing the sort of "British" face you see in the best tobacco advertisements, and had been told he was a cub producer, learning the job. He had not been about the place long before he was cub-producing his own voice as a compere; but before he really had time to get a hold on listeners in that role, he had got the television announcer's job.

This was Leslie Mitchell, a young actor by training, not long back from a tour of "Journey's End" in which he had played Stanhope. He it was whom viewers saw first on their screens; the engineers at Alexandra Palace started testing the transmitter straight away, and got Leslie Mitchell to sit in front of the camera as they sent out the tests. I used to watch Leslie on what was one of the first commercial television sets in operation in London, and have always thought that the gagging act he did then, talking attractively about nothing in particular so that we kept the machine switched on, has never been surpassed in television!

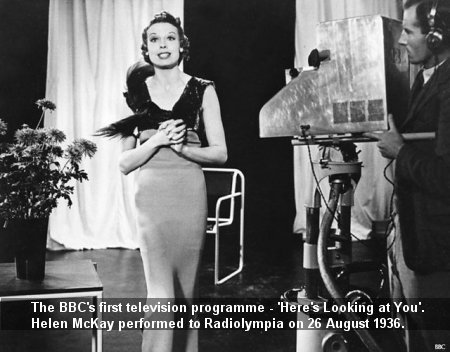

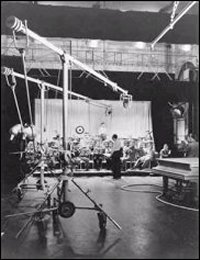

Meanwhile, Cecil Madden was organising a programme to be called Here's Looking At You! to be produced in the new studios for reproduction on the screens of new television sets at the Radio Exhibition. It was a variety programme, evolved somewhat in the cabaret tradition - a tradition which Madden was to find peculiarly suited to the intimate qualities of viewing in the home. An orchestra was of course needed, and Gerald Cock called in Hyam Greenbaum, who had been conducting in theatres for Cochran., and was husband of Sidonee Goossens, the harpist. Greenbaum got together a combination which was named the BBC Television Orchestra. Its leader was Boris Pecker, and its third fiddle a young man called Eric Robinson, brother of Stanford.

Madden divided his studio floor into four quarters, with a curtain before each. The first act started in one quarter, finished, and the curtains there closed; a second camera took the curtains rising in the second quarter to reveal the second act, and so on round the mulberry bush.

Here's Looking At You! -the first television programme from Alexandra Palace-took the air on August 26, 1936, and the first artist to appear on the hearthside screens - and those ranked for display at the Radio Exhibition - was a vocalist, Helen McKay. Later she became one of a close harmony act, The Keynotes. Helen was followed by The Three Admirals, from the show Anything Goes; and they were followed by Pogo, the Horse.

Pogo, the Horse, played by the Griffiths Brothers, has as hallowed a place in the pioneer viewer's memory as has Rex Palmer's voice in the early listener's. Pogo, mixing up his back legs in his front, was purely visual and gave the first proof, crude though it was, that television is a visual medium in its own right, and not merely a picture added to sound radio.

This first television variety bill was completed by Chilton and Thomas, a pair of swift moving Chilean dancers, and the whole was introduced by Leslie Mitchell, making his public bow as the most gazed-on man in the kingdom-an event which embarrassed him with blush-making fanmail for weeks after.

Here's Looking At You! was put on every day until the Radio Exhibition closed on September 5, and to play quite fair, it was transmitted on the Baird and E.M.I. systems alternately. The last programme transmitted to Olympia was celebrated by an outbreak of high spirits, then unique in the dignified BBC. The Three Admirals serenaded Elizabeth Cowell; Hyam Greenbaum played a violin very badly; and the engineers made trick pictures which did the oddest things to Leslie Mitchell's face. The three announcers even joined boisterously in the closing chorus. This was the first evidence of that human note which has been attractive in television, despite the Broadcasting House way of keeping broadcasting an impersonal and rather officious service. Indeed, without this freedom to let off steam at Alexandra Palace, staff and artists, crushed by the frustrations pressing on television, might have given up the ghost long ago.

There followed, in 1936, a period of tests and irregular programmes with which the first engineers and cameramen eased themselves into the demands of the new medium. One of these trial programmes was the first Picture Page, the only television feature which remained years later.

Cecil Madden, who in addition to organising the programmes, was producing a number each week, devised Picture Page out of the collision of two thoughts. One was the realisation of the success of "In Town To-Night" and "At The Black Dog," in sound broadcasting; the other thought was of a girl called Joan Miller, who had done a telephone switchboard act for Madden in the Empire programmes.

Madden had been told that Joan Miller was earning thirty shillings a week in bit parts, and was finding life a struggle and not eating enough. He had her do her "Grand Hotel, Good Morning!" act-and then saw it as a means of linking together the interesting people he was to introduce into Picture Page. Within a few months Joan was known throughout the Home Counties as "the Picture Page Girl." Later she became a much sought after actress of fine dramatic power. She took London by storm in the controversial play, Pick Up Girl.

The first Picture Page, on October 8, 1936, had Joan buzzing in through her switchboard this assembly of interesting people with stories to tell: Squadron-Leader Swain, flying altitude record breaker; John Snuggs, a theatre queue performer who sang songs and tore paper designs; Prince Ras Monolulu, the racing tipster; Mrs. Flora Drummond, veteran of the Suffragettes; Dinah Sheridan, a glamourous artist's model; and a Siamese cat, Preston Pertona. This cat's grand-daughter was televised in 1949 in a Picture Page commemorating the issue of the 100,000th television licence.

Madden was editor of Picture Page and remained so until the war closed down television in 1939. Its producer was George More O'Ferrall, who became one of the foremost producers of the classic drama on the television screen. He was replaced within a few months by Royston Money, who also became a senior drama producer.

After this first Picture Page, Marsland Gander, the Daily Telegraph. radio critic, wrote: "Mr. Cecil Madden and Mr. More O'Ferrall have found the secret of successful television programmes --- human interest and rapid tempo, frequent close-ups and no overcrowding of the small screen." Though experience has found that television requires more than this, the recipe is still valid to a degree.

Here's Television by Kenneth Baily 1950