History of the BBC - Part 2

Here's Television

Published in 1950, esteemed television critic Kenneth Baily's book 'Here's Television' is a fascinating account of the early days at the BBC. The book is written with all the authority of someone who was present when the first broadcasts were made from Alexander Palace in August 1936, up to its closure in September 1939 at the outbreak of war, and its subsequent re-opening six years later. It is lent more weight by the fact that it was written a short time after these momentous events, when all the facts were still clear in his memory. This absorbing and detailed account of the early days at the BBC is an important part of British television history.

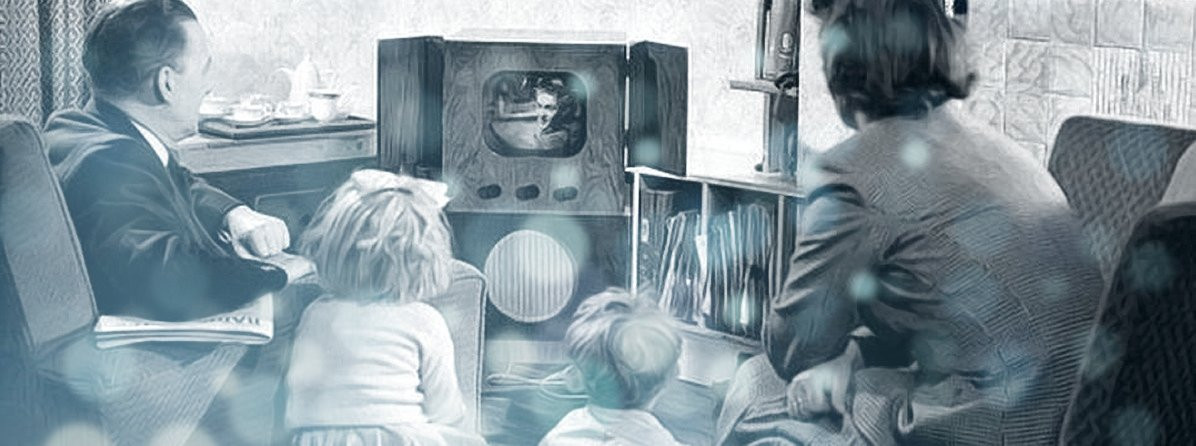

Most people had gone to bed. Some perhaps listened drowsily to Henry Hall and the BBC Dance Orchestra playing the late night dance music. In London's West End the theatres had closed their doors, and sent the people home talking about Ivor Novello in "I Lived With You," Frank Vosper in "Musical Chairs" and Tilly Losch in "The Miracle."

Ramsay MacDonald was Prime Minister; Franklin Roosevelt was campaigning for the presidency of the United States; Amy Johnson was making record-breaking flights over half the globe, and Gus Chevalier, a comedian from the Windmill Theatre, was being televised that night.

That was not news. Hardly anybody was looking at him. Few cared about television in 1932.

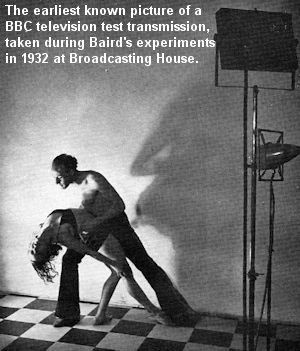

The BBC had given over a studio, in the basement of Broadcasting House, for television programme experiments. It had shown interest in television three years before that, when it gave transmitter facilities to a pioneer company, called Baird Television Limited, to transmit pictures from the company's own studio in Long Acre. Those transmissions were through the medium-wave London transmitter.

There were no television sets on the market, but a hobbies magazine told you how to make one for yourself, and a few people had achieved the extraordinary feat. In 1927 a picture had been sent by wireless over a distance of 250 miles in the United States. The news had been received with sarcastic scepticism.

Twelve months before that, John Logie Baird had sent images short distances by his own television transmitter, which was a proper eccentric's rig-out of old tin discs, wire and string. After a few months he sent the image of an office boy through the wall into the next room. That was not news at all, but the few who heard about it were mightily impressed.

And rightly so, because eleven years later-a short enough time in the normal progress of science-thousands of people, sitting in their homes, watched the Coronation Procession of George VI and Elizabeth. I watched it myself, and remember noticing the emotional strain on Queen Mary's face. The television camera took me right up to the window of her coach.

But it is Gus Chevalier for whom I have a soft spot in my television memories-and those other pioneering artists who shared a fanaticism for television with the handful of BBC staff who were coping with those experimental programmes, below ground level at Broadcasting House. On several nights, I walked round the windy corner of Broadcasting House's prow-like frontage in Portland Place, to watch Eustace Robb put out the 30-line "low definition" television programmes, which were really the first BBC sound and vision broadcasts.

Gus, on top of a day's work at the Windmill, would allow himself to be blotched and streaked with the black and white greasepaint, then used to give sharp definition to the features. He had a white streak down the centre of his nose, black lines under his eyes, and white above. Standing in the flickering light, which threw a spot of light up and down the body, he did his lugubrious "Inventions" act, for the doubtful benefit of a score or so of fanatical enthusiasts, scattered about London, using home-made sets, on which they sometimes saw a hazardous picture six inches high by four inches wide. Nobody knew how many viewers there were.

That studio, known as B.B., had a white and black chequered floor. Across it, moving gracefully within terribly confined space, I watched ballerina Lydia Sokolova dance; saw a young child of a dancer-songstress called Betty Astell; and once - greatly ambitious - Eric Maschwitz's startling importation into the BBC's weekly "Music Hall" show, the Eight Step Sisters came and did their "taps." It is pleasing to remember how many stars gave their services to those primitive experiments, because the money in it was nominal. There were Adeline Genee, Sandy Powell, Delysia, Carl Brisson, Devika Rani, Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin-and Josephine Baker!

The Studio B.B. programmes, from eleven to eleven-thirty on four evenings a week, were conducted by Eustace Robb, a BBC man with a faith that television had in it the future of radio. He had been a Coldstream Guardsman, and had the figure for it, which he always took care to clothe elegantly. With him was the first BBC television engineer, Douglas Birkenshaw, whose like faith in "the ultimate form of radio" took him to the position of Senior Engineer in Charge at the BBC Television Station at Alexander Palace. When the BBC took up television seriously, and opened the daily service at Alexandra Palace, Eustace Robb left the Corporation. Whether he or they were right in the disagreement there was, it seemed a pity; as television has reached each milestone I have always missed him.

By 1934 Robb's experimental programmes had to be taken seriously, one way or the other. The BBC, never rash with money, had to decide whether it was backing a winner or a loser, down there among the greasepaint and flickering light in the basement. The studio had been equipped because there was "sufficient technical interest" in television to merit, tests. That kind of interest was certainly abundant. A number of radio apparatus manufacturers had all along been devising methods of television transmission and reception. But the Corporation, a public service, had to decide whether the thing had programme value.

It was perhaps as well that the entertainment value of the 30-line "low definition" programme was negligible. The results on the tiny screens were received more as evidence that a new kind of radio conjuring trick, did in fact work. Had there been a realisation that television had arrived, with its consequent conclusion that sound radio was due to become a back-number, the BBC might have taken some degree of fright!

What the BBC did was to refer television to the Post Master General, its government liaison and spokesman. It could not ignore the technical interest, or the large sums of money radio manufacturers were sinking into their experiments. Furthermore television was "wireless telegraphy," of which the BBC had valuable and monopolistic operational rights under its licence. If it did not take steps, somebody else would, possibly backed by the radio manufacturers-and the government might have had to deal with a request to licence a rival organisation!

The government action was to ask the Post Master General to set up a committee to report on the merits of several systems of television transmission (not on Studio B.B.'s programmes!) These were the systems being developed by the manufacturers. Lord Selsdon was chairman of the committee, a learned judge, adept at sifting evidence. There were four scientists, a BBC representative and one from the Post Office; and the group called thirty-eight witnesses, including four radio manufacturers.

It was this committee, dealing with television on a technical basis, which recommended that a public service of television be started by the BBC, from a station in London. Of the systems submitted to it, it selected the Baird and the Marconi-E.M.I. systems, laying it down that the BBC programmes were to be transmitted on both systems alternately - Baird one week, and E.M.I. the next. The Baird system was of 240 lines definition; the E.M.I. of 405. This meant that radio manufacturers had to turn out sets capable of receiving both types of transmission, and that the BBC television station would have to have two different studios and two transmitters. Even the make-up of artists would have to be different for each system.

The last point was hardly one to reach government committee level; but it is interesting, and I think important, that this first investigation of television was pre-eminently a technical one. The question of what programmes television should supply, with all the attendant implications as to its power in the home, culturally, educationally and as a medium of persuasion - these questions only began to receive much later. Obviously there was next to no evidence to go on as to programme content and impact, but what had happened had established the tradition of television control in this country. Government interest has all along been predominantly technical and legalistic, it being left to the BBC to tackle the social problems inherent in television's nature.

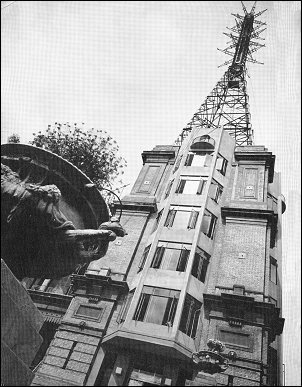

It was now the BBC's job to find a site for the first Television Station, and it selected Alexandra Palace. Six miles from Charing Cross, the Palace sprawls along an emparked hilltop, 306 feet above sea level, over the suburbs of Wood Green and Muswell Hill, for the benefit of whose populace it was erected as an entertainment and exhibition centre. I always regard it as the final, rather hopeless fling in the Victorian style of institutional building - sentimental idealism frozen into ugly pretentiousness, guarded by characterless statuary of sparsely dressed women and be-toga-ed men with prodigious beards. It was becoming a white elephant, and its trustees were no doubt very pleased to lease one wing of it to the BBC for this new television business. They could not have known that this was to be the most revolutionary Alexandra Palace "exhibition" of all time.

The BBC took over 55,000 square feet; the south eastern wing and tower, and what is known as the Theatre Block behind. Like most of the building, the wing was decrepit, full of cobwebs, peeling plaster and broken statuary. The musty, bleak tower had become a hollow mockery of any past grandeur it may have had. This tower was decapitated so that the television aerial mast could be built on it.

In those days of plentiful materials, the mast grew with remarkable speed. Suburbanites, travelling to and fro on the LNER line down at Wood Green, watched its progress from their railway carriage windows, and flew into arguments about the good or ill of television, based entirely on imaginary premises, because, of course, nobody yet knew anything about television.

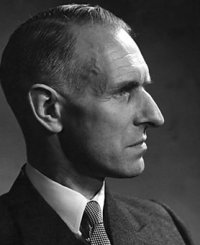

The mast, starting 30-feet square at the base, tapered up to stab the sky 300 feet from the foot of the original tower-or 606 feet above sea level. To meet gale pressure winds it had to be anchored in seventeen tons of concrete, and fastened to 50-feet anchor girders down each corner of the tower. One of these swept down through the office of Gerald Cock, who had already been chosen at Broadcasting House to take charge of television. Gerald Cock had built up the BBC's Outside Broadcasts Department from its early beginnings -a man of superlative tact, because in doing that the BBC had faced the acute rivalry of the Press. He had adventured in gold mining and ranching in Utah, Alaska and Mexico, and had been an extra in early Hollywood films. A bachelor, there dwelt behind hip exquisite manners and sartorial excellence, a very determined character indeed.

While the finishing touches were being put to the premises up on the windy hill above Wood Green, Cock called together, round a table at Broadcasting House, the handful of men he had chosen to be the first BBC television staff.

There was Cecil Madden, who had for some years been organising the sound programmes which were sent out at all hours of the night to the far flung Empire. D. H. Munro had been a studio technician at Broadcasting House, and was now destined to develop one of the most fertile imaginations television was ever to find. But obviously the BBC was weak in men with practised experience of the visual entertainment world, and Cock wisely looked to the theatre business for most of his recruits. From Drury Lane he brought in Peter Bax, a stage manager with a flair for scenic design-and later the Head of Design at Alexandra Palace. From the London Pavilion, then a variety house, he brought in another stage manager, Harry Pringle. Two very young men, George More O'Ferrall and Stephen Thomas, came from theatre production jobs, the latter with valuable experience gained under Sir Nigel Playfair at the Lyric, Hammersmith. To these was added Cecil Lewis, a tall, dynamic and unpredictable type who had a flair for ideas and an idealism about education.

George More O'Ferrall later became a senior drama producer in television, winner of an "Oscar" given by The Television Society for the best production of the year. Stephen Thomas joined the Arts Council. Cecil Lewis was last heard of in Tahiti, for his flair was accompanied by a wanderlust which would never let him stay long in one place.

These men felt themselves to be fortunate, for not only were they on the threshold of what they knew must be the biggest development in broadcasting since 2L0, but the BBC was giving them plenty of time in which to prepare. Gerald Cock sent them up to Alexandra Palace saying: "You've quite four months before we start programmes; begin planning, and take your time over it. Find out all there is to know about cameras, lighting and the rest of it - let us start with slickness and efficiency, if not with experience."

Madden was Programme Organiser, and as he sat down in his new office, high in the tower at Alexandra Palace, he relished the opportunity of several weeks calm and unrushed atmosphere in which to build up the first television programme. His telephone rang; it was Cock. "Forget everything I told you," he said. " It has been agreed that we produce programmes for the Radio Exhibition at Olympia. It opens in four weeks' time."

From that moment a fever of activity hit the Television Station, and the war apart - never left it.

Source: Here's Television by Kenneth Baily 1950