History of the BBC - Part 4

The Official Start

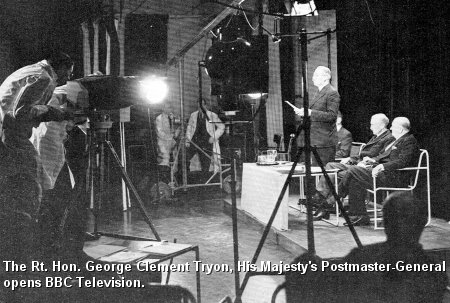

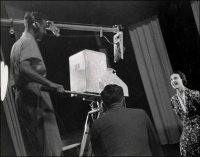

The BBC decided that the official start to the Television Service proper should be on November 2 1936, and it laid down the red carpets at Alexandra Palace and had the thing done in style, with an opening ceremony before the cameras performed by a strangely mixed company.

Lord Selsdon, judicial chairman of the Government's television committee, the Post Master General, and the chairman of the BBC governors were joined by Adele Dixon, singing, and by a coloured pair known as Buck and Bubbles, dancing. But viewers possibly had better entertainment from the second edition of Picture Page which followed the ceremony, and introduced them to airman Jim Mollison, Miss Kay Stammers, Algernon Blackwood, a pearly king and queen from Blackfriars, and -for their first off-duty appearance- Elizabeth Cowell and Jasmine Bligh, the announcers.

Behind the scenes misfortune had dogged that grand opening night. Gerald Cock was away ill. Jasmine Bligh, recovering from appendicitis, defied doctor's orders to help with the show. Then an accidental cutting off of the main water supply to Alexandra Palace caused a breakdown! The technical difficulties so piled up, in fact, that the next day the BBC cancelled all programmes for the remainder of the week.

At the beginning of the next week a fresh start was made, with excerpts in the studio from The Two Bouquets, then at the Ambassadors Theatre.

Looking back, it is remarkable how, in that very first week of programmes, all unknowingly foundations were laid for what were to become some of the main features of television broadcasting for years to come. Picture Page was broadcast until 1952; Algernon Blackwood became the ace of television story-tellers; and the week was completed by the first televised ballet, performed by the Mercury Ballet Company, and the first televised play, Marigold.

Picture Page came to be regarded almost as familiarly as The News on sound radio; but in those premier years of television the early viewers owed it a debt for never failing to bring them face to face with the people who had made the news headlines every week. Leslie Howard, Vicki Baum, A. J. Cronin, the Aga Khan, Amy Johnson, Andre Maurois, Jean Batten, Negley Farson. Stefan Zweig and others were the celebrities of those immediate pre-war years.

From November 1936 onwards the BBC printed the television programmes in a London edition of the Radio Times, and at the beginning of 1937 its editorial pundits got so worked up about television that they lavishly introduced a 16-page Television Supplement, printed in sepia photogravure. That the venture was a little too lavish was born out by its sudden disappearance later that summer. Following it, the week's programmes were squashed into one ill-arranged page, and for some months, television was editorially soft-pedalled by the BBC.

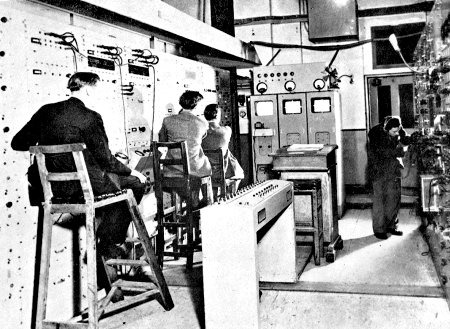

There was no damping of enthusiasm at Alexandra Palace, however. In fact, before the war and since, one of the most inspiriting qualities of the work there has been the gay indifference shown towards the rather crotchety caution, often evident at Broadcasting House whenever television has been up for consideration. The staff was growing; and engineers and cameramen were getting to know the studios and the equipment - as well as the vagaries of the Baird system, which was soon privately pronounced as inadequate;` and more and more adventures in television programme-making were being begun.

The transmissions were between three and four o'clock every afternoon, and between nine and ten o'clock every evening. There was no television broadcasting on Sundays. There was not adequate space at Alexandra Palace for the full rehearsal of productions; but there was the added limitation of changing the studio organisation, and to some extent the production technique, each week for the alternating systems of transmission. Also, the performing fees were not very good, and artists could not be expected to give time to long rehearsals. Nevertheless, in addition to simply presented cabarets, play excerpts, and talks, advances were made every month in new forms of television production technique.

Armistice Day fell within a fortnight of the official opening, and Cecil Lewis produced a programme of which Leslie Baily, the radio critic of the London Evening News, wrote:

"From the London Television Station last night was broadcast the most deeply-moving Armistice Day programme I have ever heard from the BBC. It took the form of scenes from the German film ` West Front 1918,' followed by scenes in England in peace-time, and it ended on that note of dedication for the prevention of another catastrophe which most people have felt so strongly this Armistice anniversary. These vivid, and at times terrible pictures, were accompanied by an admirable commentary spoken by Cecil Lewis . . ."

Even so soon, television was showing its power to take hold of people as a dramatic medium capable of causing emotion and inspiration.

Another Cecil Lewis exploit, before the end of that year, was The Pattern of 1936. This he styled "a review of trade, unemployment, etc., in the form of a discussion." John Hilton did the talking with Lewis. It must have been one of the first attempts to tackle what is perhaps the most difficult job in television-the attractive illustration of a mainly abstract subject. The presentation, by means of charts and film shots, may have been crude compared with what is done today, but Lewis had already begun the process of selecting from many facts and arguments just those which could be illustrated, without throwing the total discussion out of proportion.

Films were introduced into television programmes from the start. The first Television Film Unit was headed by Major L. G. Barbrook, who even before Alexandra Palace was on the air, had filmed the building of the aerial mast, piece by piece. Not until 1938 did the Film Unit take more than occasional outdoor background shots, which were sometimes required to give atmosphere to a studio programme. For example, to provide a few seconds of atmosphere in one of Harry Pringle's Eastern Cabarets, they filmed an airliner taking off at Croydon. The cameraman was perched on top of the film car as it moved alongside the plane at 45 miles an hour. In 1938 the Unit made the first sound-film as an integral part of a television production. Outside action shots were taken for Cyrano de Bergerac.

There was no BBC Television Newsreel before the war. Gerald Cock had negotiated successfully with Movietone News and Gaumont British News to show their current news reels several times each week. The film business had not yet grown cautious about television's effect on the cinema box office as to become completely obstructive. It was because the film companies banned the televising of all newsreels, after the war, that the Television Newsreel Unit was formed.

In light entertainment a very early scoop was the televising of Sophie Tucker, when she was in Britain in 1936. The same night the Sadlers Wells Ballet Company was in the studio. Sophie watched them on the screen: "Say...!" she said, "this BBC television's just amazing! In another year it'll be a finished product. There's nothing in America like you have here."

Bebe Daniels and Ben Lyon made more than one appearance; and by the end of the first three months of television, those first viewers had seen: Frances Day, Yvonne Arnaud, Claude Dampier, Edward Cooper, The Western Brothers, Bowyer and Ravell, Anne Zeigler, Robb Wilton, Gillie Potter, Lily Morris - and, in a short afternoon cabaret, Googie Withers, who at that time was quite unknown in the film studios.

One regular cabaret act was "Symphony in Motion," by Marion and Irma, two perfectly proportioned Scandinavian girls, whose rhythmic contortionist act will stay long in the memory. Television was then very fond of putting glamour on the screen, and London cabarets and show managements were co-operative enough to send up to Alexandra Palace such curvaceous troupes of girls as the Buddy Bradley Girls, The Albertina Rasch Girls from the Dorchester, and later, Henry Sherek's Chester Hale Girls. For a long time one of the most requested programmes was Harry Pringle's Cabaret Cruise, in which the bridge and deck of "SS Sunshine" were built up in the studio as the setting for a cabaret, presided over by that able tale-spinner, Commander Campbell, later famous on the Brains Trust.

The only damage done by a gale to the Alexandra Palace aerial mast occurred in 1936. A full day's transmissions had to be cancelled because a 90 miles an hour wind caused spacers between the aerial wires to bend and short circuit. In spite of the gale, engineers climbed 200 feet up the mast, and tried to make repairs in time for the night's transmission. Studio lights had to be taken outside and pointed up the mast to guide them. But the wind made the work too hazardous, and the attempt had to be given up.

The first Christmas of television provided a programme of music hall old-timers; a television studio party; and a Father Christmas who vanished into thin air by means of camera trickery. This kind of technical effect took such a hold on viewers that later on it had to be restrained by the programme chiefs. On Christmas Day itself, at three o'clock appropriately, a chef demonstrated how to carve a turkey!

I believe few at Alexandra Palace in those days would have prophesied that plays were to become television's most popular fare. In programme planning drama lagged behind variety. It was quite an event when George More O'Ferrall - still known as "the Picture Page producer filled half an hour with Reginald Berkeley's The Tiger, in which "a brilliant young actor" William Devlin played the old French statesman Clemenceau. Joan Miller was in the cast. O'Ferrall's next step in his rapid ascent as a drama producer was to present Robert Speaight in Murder in the Cathedral, then at the Duchess Theatre. This is the earliest recollection I have of a really inspired use of the close-up in television drama. There was also that Irish comedy, The Workhouse Ward, played by Sara Allgood, Tony Quinn and Fred O'Donovan-Who later became a producer at Alexandra Palace.

Several of the then famous dance bands were televised. It was not until 1947 that the BBC really made up its mind that viewing a band playing "straight" is seldom good television. In the musical sphere, masques and operatic excerpts were found to be more suitable material; and there was one early attempt which had in it the germ of the "Casa d'Esalta" programmes. This was Cafe Cosmopolitan. Though based on the hackneyed formula of putting a light orchestra into a romantic setting, and "dressing" it with gentlemen in cloaks chatting to pretty ladies over little tables, it did show that decor and movement are required if an orchestra or band is to be satisfactory on television.

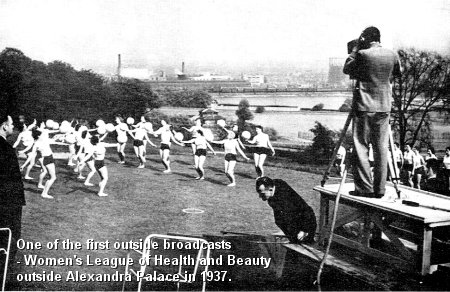

The Park, at the doors of Alexandra Palace, with its groves, almond trees, alfresco cafe, and pond, soon began to tempt the pioneers of outside television production. All the first outside broadcasts came from there. For some time it was thrilling enough to watch the picture which was obtained merely by swinging a television camera over the view to be seen from the studio balcony. Northern-bound expresses could be watched distinctly, getting up steam on the railway line down at Wood Green. But the camera could not long be kept within bounds.

Within ten weeks of the start of television, Cecil Lewis had taken cameras outside, at night. He provided an actuality programme about anti-aircraft defence. The 61st (11th London) AA Brigade RA demonstrated two ack-ack guns; and the 36th AA Battalion RE handled three searchlights, while RAF planes were specially flown over the Palace.

This co-operative "exercise" staged "a short action repelling the attack of hostile aircraft." The very wording of that programme announcement breathed something of the oddity which most of us found in an exploit that seemed far from reality in 1936. Four years later the flash and crackle of a much mightier barrage surrounded the Alexandra Palace, and echoed through television studios emptied by a real war. '

Source

Here's Television by Kenneth Baily 1950